Queensland is famous for two things: the largest coral reef on the planet and the world’s oldest rainforest. But there’s another claim to the state’s environmental fame. Deep in the savannah landscape southwest of Cairns, where Triassic granite outcrops intersperse with legions of “Star Wars”-style vermilion termite mounds, and within coo-ee of the Dinosaur Triangle — an area of shield volcanoes that erupted 270,000 years ago — lie the oldest standing lava tubes on earth and the longest lava flow from a single volcano in modern geological time (an incredible 164 kilometres long). This supports a delicate eco-system and unique vegetation that traces back to Gondwana — the same flora species are found in the famous lava tubes of Madagascar.

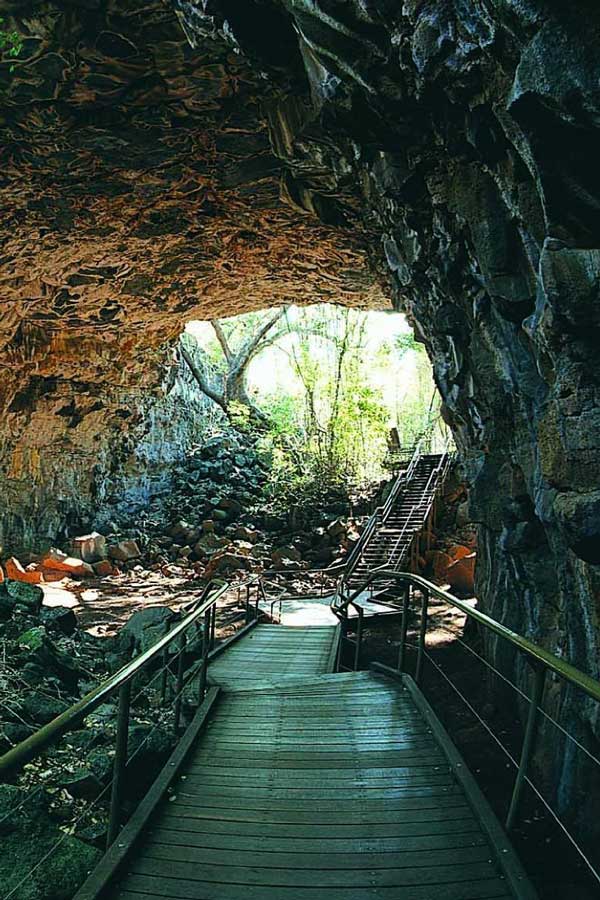

When I first arrive at Undara Volcanic National Park, I meet Savannah guide and laconic bushman Bram Collins; this is his backyard. For six generations his family has protected this area, and as owner of Undara Experience, he is dedicated to the cause of preserving these lava tubes. Together we descend a set of wooden stairs, away from the dry, crusted land to the path of a volcano. As I enter the rift of an otherworld, I see thousands of yellow butterflies flit amid the flow of green pandanus, strangler figs and ferns. The air is different. The sounds are different.

I’m lost in time walking beneath the multicoloured lava arch that interlocks like Lego, its heat-scarred walls pitted with gas-popped basalt and nipples of cave coral. Through the tangles of vines and thickets I enter Stephenson Cave. To me, as awe-inspiring as the Sistine Chapel, yet created nearly 200,000 years earlier. It’s easy to understand why upon witnessing the magnificence of the Undara lava tubes in the 1990s, Sir David Attenborough declared them one of the most “unexplored geological features of the earth”. He went as far as to declare they should be the eighth Wonder of the World. I agree.

After a night in a refurbished vintage Queensland Railway carriage nearby and a bush breakfast around the campfire, I trek into Barkers Cave, near Undara Volcanic National Park’s western boundary. This is a maternity cave for microbats and their young, and as I stand witness to the nightly foraging migration of tens of thousands of microbats pinballing around the cave, I notice the draping tree snakes at the cave’s entrance which see these bats as self-serve fast food. The sound and movement is mesmerising and meditative.

On the return trek, I spot seven species of macropods, including the whiptail and pretty-faced wallabies, before arriving at Sunset Bluff to sip champagne and snack on cheese. From there, I scan the 81,000-hectare Rosella Plains cattle station encased within the Undara Volcanic National Park. Looking at that expanse, I recall a passage by the English author Robert Macfarlane from his lyrical tome of landscape and deep time, “Underland”:

“Down between roots to a passage of stone that deepens steeply into the earth. Colour depletes to greys, browns, black. Cold air pushes past. Above is solid rock, utter matter. The surface is scarcely thinkable.”

He could have been describing Undara, the caves, this area and my feelings.

Archway into the Eden of the collapsed lava tube. Photography courtesy of Undara Experience.

Archway into the Eden of the collapsed lava tube. Photography courtesy of Undara Experience.