In 1847, Louis-François Cartier opened a modest jewellery workshop in Paris where he sold crystal bracelets, strands of pearls and brooches with floral motifs. Over the decades, his three grandsons, particularly the eldest, Louis Cartier, became known for mixing Old World craftsmanship and new techniques, as in the 1904 Santos pilot’s watch, named for a pioneering Brazilian aviator and decorated with tiny screws resembling airplane rivets; or the so-called mystery clock, a timepiece popularised by the brand in 1912 with jewelled hands that appeared to float (its rack-and-pinion gear system was hidden in the base).

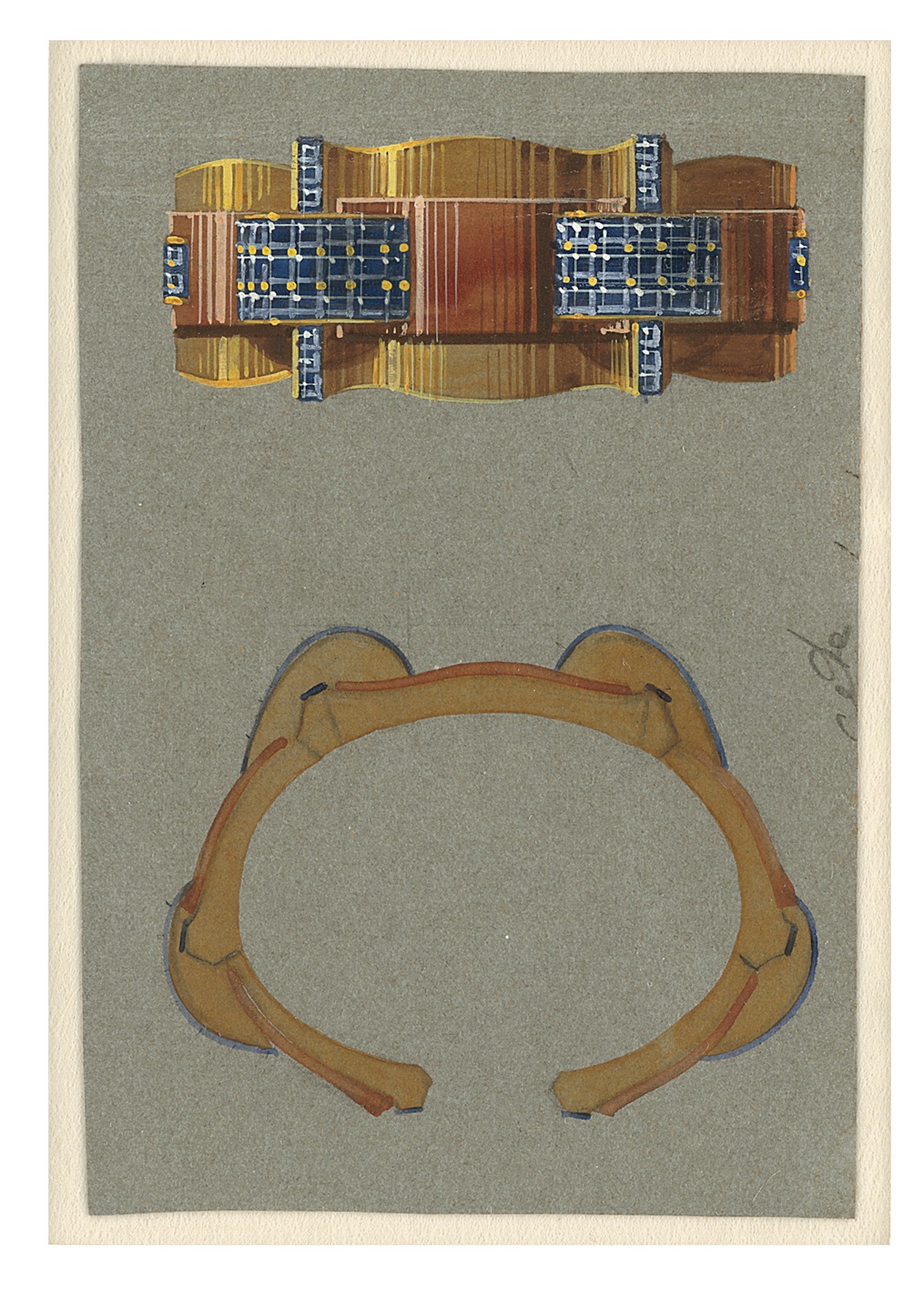

In 1914, Louis Cartier met Jeanne Toussaint, the Belgian French style icon who would become his muse and rumoured lover. Often immaculately dressed in her signature turban and silk pyjamas, she captivated Cartier, who recruited her to oversee the house’s handbags and silver accessories. When Toussaint was appointed the creative director of the brand’s jewellery department in 1933, she, too, found unlikely inspiration in utilitarian objects: gas hoses, bolts and even handcuffs. In 1938, she created a yellow-gold cuff bracelet entwined with sapphires that resembled the interlocking shape of a shackle and reflected her fascination with Indian Mughal jewellery.

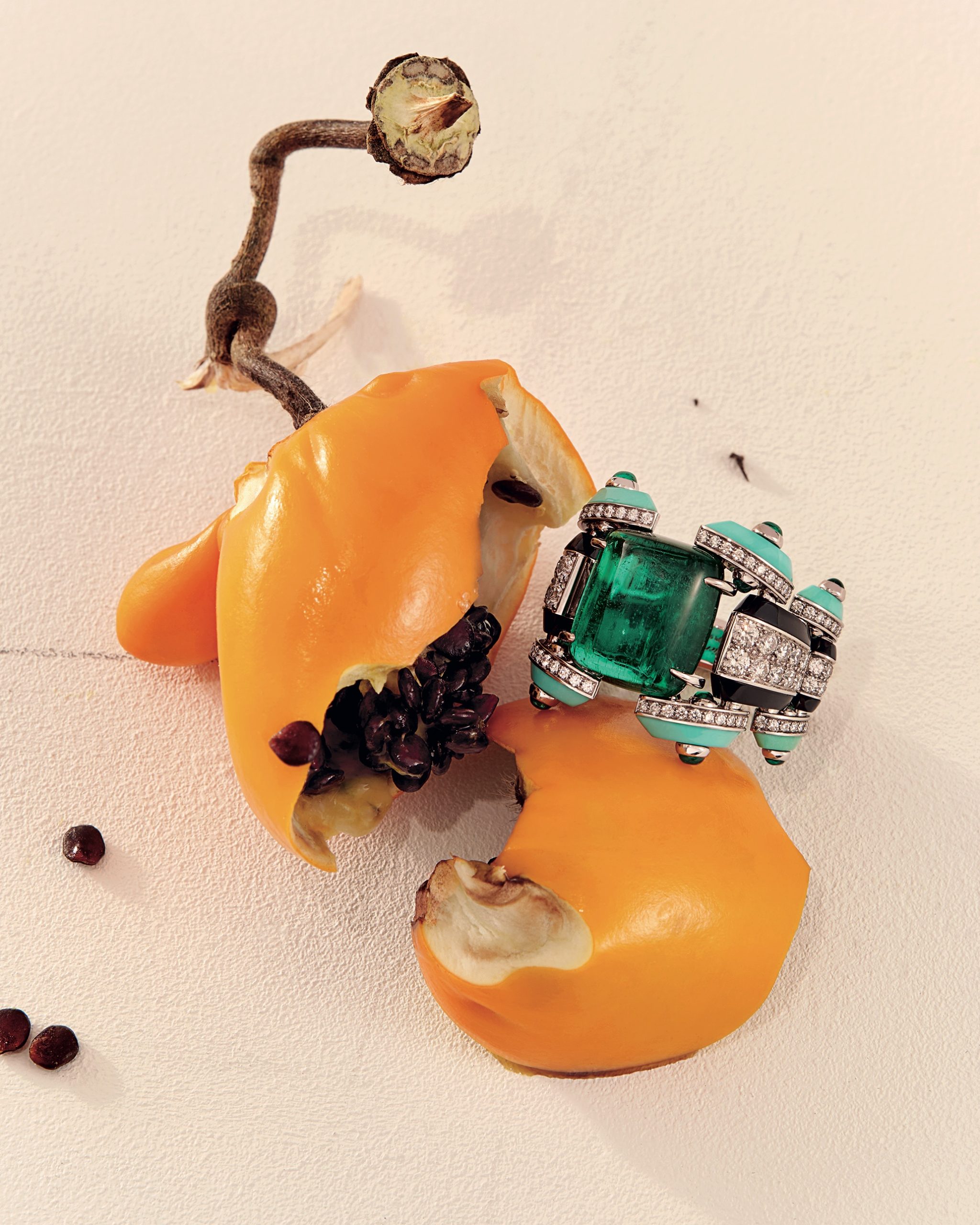

Now, Cartier is revisiting Toussaint’s archival designs in the form of a ring topped with an 8.92-carat cabochon-cut emerald encircled by rounded onyx, diamonds and turquoise accents. Requiring 270 hours to produce, and with a three-dimensional silhouette that evokes the look of mechanical ball bearings, it’s another feat of sculptural engineering from a house that was built on innovation.