Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people should be aware that this article contains the names of deceased persons.

In March 2020, as cases of the novel coronavirus started to proliferate in Australia and the nation retreated into its first lockdown, live performances were cancelled and cultural venues were shuttered. By April, more than 50 per cent of arts and entertainment businesses had ceased operating. Further lockdowns of varying lengths and severity across the states — not to mention the 704-day international border closure — compounded the pressure on an industry already straining to accommodate unstable funding and a precarious gig economy.

Almost two and a half years on, the effects of the pandemic on the country’s creative sector are yet to be fully understood. Data gathered by government and industry bodies tells a story of cascading cancellations, disproportionate job and income losses, and billions of dollars in missed revenue for one of the worst-affected industries. The future of the arts in Australia is as elusive as ever.

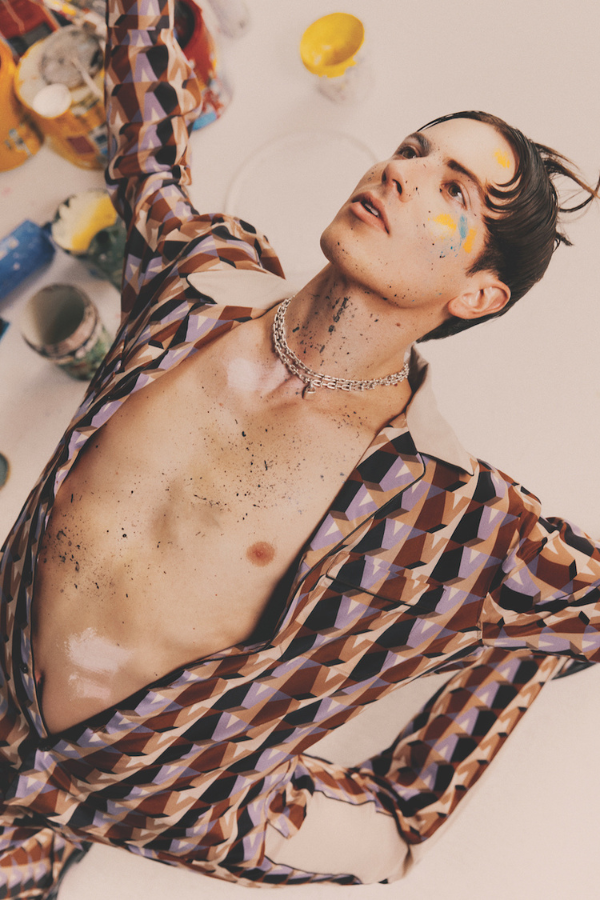

When the first lockdown happened, the Australian dancer and model Rhys Kosakowski had just joined the Sydney Dance Company after almost eight years working overseas — first with the prestigious Houston Ballet, which he joined at age 17, then in Los Angeles, where he expanded his modelling career and burgeoning public profile.

“I got a few months of normality and then it hit,” says the Newcastle-born classical and contemporary dancer, who rose to fame as a 13-year-old playing the titular character in Australia’s “Billy Elliot: The Musical” (he was the first to perform the role outside the United Kingdom). “I was just happy that I was in the company, and by then I’d made such a family and had such a friendship group.

“No-one has really gone through something like that before,” he continues, “but it was amazing to see how well the company stuck together, just doing what we could to stay afloat, like teaching and working online. I didn’t feel alone.”

Having returned to Australia with an international outlook, Kosakowski, 27, believes that in order to thrive, the local arts scene must focus on what makes it unique. “I think we need to push our Australian identity, as dancers, to keep creating and keep being inspired and keep doing what you don’t see, because that’s what’s so appealing,” he says. “We need to really be our true self and keep pushing it. Hopefully, it will be seen by people overseas, which means it will travel throughout the world.”

The new federal arts minister, Tony Burke, shares Kosakowski’s vision of Australia as an exporter of culture. When the Labor government came to power in May, it did so with a mandate to re-prioritise the arts. Burke has said he is “determined to deliver a better future for Australia’s creative sector”, however questions remain over spending allocation.

It comes in the wake of a coalition government that oversaw damaging cuts to the Australia Council for the Arts and the ABC, merged the federal arts and transport departments before announcing plans to double the cost of humanities degrees in 2020 and, most recently, reduced arts funding by approximately $190 million in its March 2022 budget.

Granted, initiatives such as JobKeeper, the JobSeeker Coronavirus Supplement and the RISE Fund, introduced by the Morrison government, played a part in offsetting some of the pandemic’s negative impacts for those who qualified. But they do not redress years of systemic erosion of the cultural sector, much less guarantee ongoing security, notes Ben Eltham, the co-author of an influential report by The Australia Institute’s Centre for Future Work titled “Creativity in Crisis: Rebooting Australia’s Arts and Entertainment Sector After Covid”.

“The stimulus is winding down and the emergency funding that was put in place is winding down, but the pandemic is still with us and you’ve got a lot of uncertainty going forward,” says Eltham, who is a journalist, researcher and lecturer at Monash University’s School of Media, Film and Journalism. “Whatever measure you look at, it’s not back to 2019 levels. A lot of people have simply left the industry, particularly technical workers, production workers, crew. So there’ll be long-term impacts from that,” he says. “In our recommendations for the report, what we were saying is we need to use the opportunity of the crisis to try to reset and reimagine the policy architecture for Australian culture, and set it up for a sustainable longer-term future.”

In July, the federal government began accepting public submissions for a new National Cultural Policy. The invitation arrived with five goals, beginning with a commitment to recognise and respect the place of First Nations stories at the centre of our arts and culture. A draft report by the Productivity Commission, which found that local and international interest in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander visual arts and crafts generated $250 million in sales in 2019-2020, but that Indigenous people received only 10 to 15 per cent of this, is indicative of the work to be done.

For Bangarra Dance Theatre, the reopening of international borders promises a return to overseas touring, with Covid-19 having paused a decades-long tradition that allows the company to share Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultures with the world. While an international touring schedule is yet to be announced, Bangarra’s outgoing artistic director, Stephen Page, regards it as a cultural responsibility. “We are one of very few [companies] that truly can say we celebrate our heritage,” he says.

“Most Western countries globally usually have an awakening experience,” explains Page of Bangarra’s impact on international audiences. A descendant of the Nunukul people and the Munaldjali clan of the Yugambeh Nation, Page says undertaking song and dance workshops with other First Peoples around the world also presents an opportunity to exchange knowledge. “There is a strong similarity with our global First Peoples audiences who are empowered by our stories,” he says.

Arts and cultural initiatives in remote Indigenous communities have also suffered significant setbacks due to pandemic closures, with stringent distancing measures, designed to protect communities from Covid-19, affecting access to shared spaces and income from arts tourism. On Gija Country in the East Kimberley region of Western Australia, the world-renowned Warmun Art Centre closed its doors in 2020 and later pivoted to a digital exhibition model to regain some level of momentum.

The centre, which was established in 1998 by the late founding members of the contemporary painting movement in Warmun, including Rover Thomas, Queenie McKenzie, Madigan Thomas and Hector Jandany, is owned and governed by the Gija people, with all income going to the community. Among its revered senior artists are Mabel Juli, Lena Nyadbi, Shirley Purdie and Patrick Mung Mung.

It reopened in May after two years and two months. Eileen Bray, the organisation’s chairperson, says the lockdown was keenly felt by some. “The senior [artists], they were a bit upset about it. Because the arts centre was locked down and the paintings weren’t sold, and they weren’t doing their painting much.”

Bray, who is also a language teacher and translator in the Warmun community, speaks via phone from the centre, where background laughter and the interruptions of arriving customers hint at the reinvigoration of a vital cultural hub. “It is back to normal for us community and artists,” she says, adding that buyers are now coming in five days a week.

Throughout the pandemic, international interest in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander artists has remained strong. London’s Tate Modern is currently showing “A Year in Art: Australia 1992”, an exhibition that explores Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples’ relationship to Country and colonisation’s bearing on issues of representation, social injustice and the climate. In July, new works were acquired and added to the show, including pieces by Juli, of Warmun Art Centre, as well as the senior Yolŋu artist Noŋgirrŋa Marawili, the Kokatha and Nukunu artist Yhonnie Scarce and the Waanyi artist Judy Watson.

Across the channel, Paris’s Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain is hosting a major solo survey exhibition of the Kaiadilt artist Mirdidingkingathi Juwarnda Sally Gabori. Each one of the 30-odd monumental works were painted over the course of a prolific decade, after Gabori began painting at the age of about 80. The exhibition is augmented by an online project that was created in consultation with the late artist’s family and the Kaiadilt community. According to the foundation, it’s the most exhaustive archive of Gabori’s history.

In Australia, recognition of First Nations arts and culture hasn’t been linear. “I think it’s changing. I don’t think it’s fully there yet,” says the multidisciplinary artist James Tylor, whose contemporary visual arts practice explores representations of Australia from the perspectives of his multicultural heritage, which includes Nunga (Kaurna Miyurna), Māori (Te Arawa) and European (English, Scottish, Irish, Dutch and Norwegian) ancestry. Last year, he started the influential Blak List MONA petition, calling for organisational reforms at the nipaluna/Hobart gallery and its associated festivals, Dark Mofo and MONA FOMA, after the gallery commissioned a work by the Spanish artist Santiago Sierra that asked for blood donations from First Nations peoples.

Tylor has been advocating for the recognition of Indigenous placenames for much of his career. The artist says he’s still adjusting to the speed at which they’ve recently been adopted, particularly in Australia’s capitals. “I feel like in the last couple of years, things that we really struggled with advocating for as Indigenous cultural makers, there’s mainstream advocating that had never been there before.”

As to where he’ll next direct his energy, Tylor says, “I think the cultural change that really needs to happen in Australia is the move away from specific industries in the cultural and creative sector. As an Indigenous person, I practise culture … If you think about pre-colonial ceremony, it was all-encompassing of the weather, and the food that was in season would be at the ceremonies, and then the dance and the painting, and the song and everything — they knew no limits.”

Tylor says the dividing of cultural and artistic disciplines, particularly as requirements for grants and funding, can place limits on the expression of culture. As has been highlighted by the pandemic, the siloing of the country’s cultural industries also has negative impacts for artists seeking other forms of support, with financial aid structures incompatible with gig work and the flow of many creative careers.

According to the Australia Institute’s “Creativity in Crisis” report, more people work in the country’s arts and entertainment sector than in either finance or aviation. The report also shows that four times as many Australians work in the arts and entertainment sector than are employed by the coalmining industry.

But to solely focus on economic merit risks forgetting culture’s inherent value, says Eltham. “One thing that gives me hope is that art is actually popular. You know, more people go to art galleries in Australia than go to football matches.” Several years ago, Live Performance Australia released a report stating that almost 19 million tickets were issued for live artistic performances in Australia in 2016 — a figure that eclipsed combined attendances at every major sporting code including AFL, NRL, soccer, Super Rugby, cricket and NBL.

Australia has a history of pitting the arts against other industries in discussions of national identity. But efforts to strengthen the arts sector would benefit from bridging such cultural divides, assumed or otherwise.

In March last year, the inaugural Incognito Art Show was held on Gadigal Country. Thousands of A5-size works were donated by established and emerging artists, and every piece was priced at $100, whether by a prominent figure such as Ben Quilty, Laura Jones or Reg Mombassa, or a relative unknown. Lines of buyers attended. Proceeds went to Studio A, an art space that aims to tackle the barriers faced by artists with intellectual disabilities.

The fair was such a success that a second show was held in June 2022. At Incognito, each artwork is anonymous; buyers only learn the artist’s identity after they’ve purchased the work. Those browsing are asked to simply choose the art they love on face value. “The Incognito concept is the element of not knowing who the artist is, and the flat pricing, that gives the average person the permission to engage in art,” says David Liston, one of the co-founders, who launch the initiative with hopes to support an arts industry in crisis and improve access to visual arts for a community eager to engage on a creative level.

Though he studied art history, Liston has spent most of his career in other industries and his connections outside the arts sector have helped inform his approach. “For some people, there’s nothing more intimidating than walking into an art gallery, and it shouldn’t be like that,” he says. “I am relatively new to a lot of this, but what strikes me is there are so many fantastic artists in Australia that more people should know about.

“I think there’s often a perception that the arts are competing for an audience with sports and things like that,” he adds. “But I think the reality is that arts professionals like myself need to keep innovating and finding ways to broaden our audience, because there is hunger out there.”

A similar commitment to creating ties with the community drives Ngununggula gallery in New South Wales’ Southern Highlands. Ngununggula, which means “belonging” in the traditional language of the Gundungurra people, opened last October after 30 years of campaigning by locals. The director, Megan Monte, has been involved since July 2020, having moved from Sydney to take up the role following the state’s first lockdown. “What was really heightened for me was that we were missing out on that collective sense of coming together,” she says. “So that became a real focus for us: how can we make this place feel so welcoming and comfortable that absolutely anyone can walk in and not feel that classic intimidation?”

Monte’s approach is by no means to program “easy” art, but rather to expand the boundaries of engagement. A striking installation in the gallery’s recent “Land Abounds” exhibition saw the Western Australian artist Abdul-Rahman Abdullah’s descriptively titled sculpture “Dead Horse” (2022) presented in front of a text-emblazoned panorama of the local region, created by his brother, Abdul Abdullah. Every Wednesday, the exhibition space plays host to the gallery’s yoga program. Other regular activations include tai chi, music nights and a kids’ art club — promoted as an alternative to Saturday sports.

The gallery opened at a time when Covid restrictions meant Sydneysiders were unable to travel to the regions. Monte says this allowed Ngununggula to fortify its connection with local residents before the arrival of a bigger audience. “Reflecting on it now, it was actually quite a beautiful way to open, being a regional gallery and being really driven by the community.”

One of the sectors hit hardest by lockdowns was the music industry, with vital revenue from live performances disappearing virtually overnight. In 2020, revenue from live music was down 90 per cent from the previous year. I Lost My Gig Australia reported that in July 2021 workers in the industry were losing an estimated $16 million in income per week, and 60 per cent were looking for jobs in other industries.

“I think we are all exhausted, both in Australia and overseas,” says Jodie Regan, the founder of Spinning Top Music, a management and record company. Regan started managing bands in 2004; her roster includes notable acts such as the psychedelic-rock outfit Tame Impala. “A lot of us depended on live music to promote our artists, and our artists relied on live music for that deep connection with fans — and, frankly, just to survive,” she says.

However, in light of the return of gigs and festivals, with gradually fewer cancellations — not to mention a coup that will see the South By Southwest festival come to Sydney for the first time next year — there is hope for the sector’s big comeback, although it may return in a slightly different form. “The industry-wide commitment to rebuild, and to rebuild better, gives me a great deal of optimism,” says Regan. “The return of live music has been indescribable. Getting back to a live show for the first time literally brought tears to my eyes.

“At the industry level, it feels to me like everyone has banded together a little more and been a bit more supportive,” she continues. “We’re all sharing more information. We’re all looking out for each other. I think people have become kinder … all because we share a fundamental understanding that great music needs to continue to be made.”

The process of revitalising Australia’s arts industry is in its early stages, but the pandemic’s cultural reset has imparted new ways to improve on what came before. It’s a testament to the sector’s capacity for reinvention, as well as the passion of the artists, dancers, musicians, actors and others who are the industry’s creative lifeblood. As the world grapples with ongoing change, art’s power to open minds and connect communities is integral. But it remains to be seen whether policymakers will match their commitment with the support that’s needed to ensure the long-term health of one of our most necessary industries.

The dancer and model Rhys Kosakowski wears Common Hours kimono, Gucci pants, and Salvatore Ferragamo shoes. Photography by Levon Baird.

The dancer and model Rhys Kosakowski wears Common Hours kimono, Gucci pants, and Salvatore Ferragamo shoes. Photography by Levon Baird.