When food writer Jody Orcher received a phone call from Phaidon Press in London asking her to write a chapter on bush foods for a new book focusing on Australian food, she accepted without hesitation. “I thought to myself, ‘Oh! How exciting! This could be the start. Who knows where this journey’s taking me?’” she recalls. “I’ve written so much stuff, I want to eventually have my own bush food book.”

Bush food is a subject so close to her heart that when she sat down to write the chapter, she finished it in one weekend. “I did! I just sat down and went boom, boom, boom!” But it’s not just the ancient ingredients and recipes that she’s passionate about, in her chapter of Australia: The Cookbook, Orcher also talks about the recognition of Indigenous culture and connection to Country.

“It’s so important to recognise Country with bush foods, as they connect to identity for Aboriginal people,” she writes in the book. “When we use native foods, it’s the cultural knowledge of use and preparation that should be recognised, as it connects us to Country and people.”

The proud Ualarai Barkandji writer sat down with T Australia to talk about her childhood, her connection to bush foods and the importance of access to Country.

How would you describe yourself?

“I’m just me, an Aboriginal person. I’ve worked in Aboriginal education for a long time, about 17 years now. When I was the Aboriginal education coordinator for the [Sydney] Botanic Gardens a few years back, we’d do Aboriginal bush food cooking tours which went off – people were really excited about them. I also worked for many years with national parks, in protection of cultural heritage and Aboriginal interpretation. I was quite aware then of the politics around bush food and engaging with Aboriginal people and Country and intellectual property. Since then, I’ve been advocating for protection of culture, knowledge and recognising Country.”

Can you tell us about where you’re from?

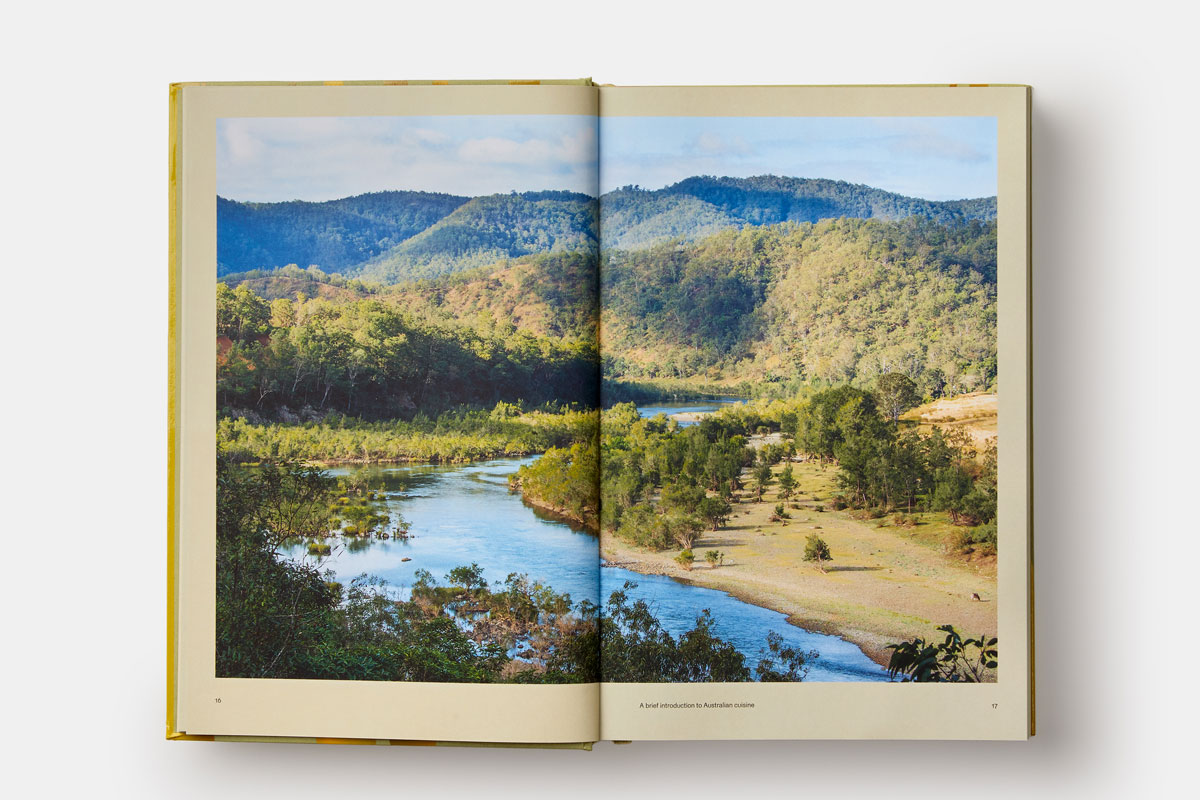

“I come from Brewarrina, north-west of NSW. It’s absolutely beautiful: semi-arid dry dessert area, beautiful red dirt, clear skies and beautiful sunsets. My mum and dad both have family from there. My great-grandparents were removed because of the White Australia policy, they were removed to the missions out to Brewarrina. So both mum and dad grew up in Brewarrina. We moved down to Sydney in 1979 and we’ve lived in Sydney ever since, but I always go home.”

What is a memory about food from your childhood?

“We always had emu! Emu is one of my favourite meats to eat. It’s better than steak [laughs]. It’s beautiful red, red meat. The flesh is more tender. It’s absolutely delicious and I love it straight off the bird, with some flour and salt and pepper, fried in oil. We have different foods throughout the seasons, to protect from any sickness: different fruits and different fats of animals – the fat of the emu and the fat of the goanna. All that fat has goodness, you could use that oil for ceremonies, men and women’s initiations, medicinal purposes.”

Over the years, have you noticed an increased interest in native foods in Australia?

“I always say to kids, ‘What are your favourite fruits and vegetables?’ and they scream them out. Then I say, ‘What are your favourite native Australian fruit and vegetables?’ and they just don’t know. Some of them know a lilly pilly, a finger lime, but they don’t know a lot. One of the most commercialised plants is the lemon myrtle. It’s an amazing plant, fragrant all year long. You can extract oil out of it, make tea, use the bark, the flower, you can use everything.”

Why do you think native fruits and vegetables aren’t as well known?

“There was this time when culture wasn’t allowed, it was a time when parents didn’t use it to protect their kids. People don’t understand that it’s not that long ago, when Aboriginal people [weren’t allowed to] speak. It’s 1967, when we had the referendum to vote – it’s not that long ago.

[Before that] Aboriginal people were restricted because they were placed on missions, or because of the White Australia policy, they weren’t allowed to practice culture. There’s this timeframe when Aboriginal people weren’t allowed to speak language. My mum used to clean the houses of the mission managers. So the girls went to work. They cut all their hair off, and you had to eat mutton and potatoes. Then on weekends, you could go down to the river and cook your traditional food.

There’s still a lot of sacred knowledge [used for] medicine and men and women’s business that’s associated to plants. It’ll probably never be shared: that’s fine. Those customs and beliefs belong to those people. The most important thing is recognising that Aboriginal people’s customs and identity are made from Country. Their traditions and beliefs come from plants, animals and areas of Country.

As Aboriginal people, we still got to work out our intellectual copyright. That’s why I talk generally. I live down in Sydney, so I’m general about the information that I talk about, but if I bring you out to my Country, we’ll use [my] language, see things, might even prepare things together. It’s a whole different experience.”

There’s booming interest in native ingredients, but only one per cent of Australia’s bush food companies are indigenous-owned.

“It’s not about bush food, it’s about access to Country. It’s about rights to water. Bush food is another thing where Aboriginal people are being used for their cultural knowledge and not to have any benefits or any employment or anything. Where I come from, there’s heaps of kurrajong seeds, saltbush, kangaroo grasses. If we could have access to those things, we could harvest them. If we could harvest them, we could have access to land. If we had land, we’d be able to sell them, we’d have jobs.”

Do you think it’s just Indigenous knowledge about bush foods that should be embraced?

“That nomadic lifestyle that Aboriginal people lived, going from season to season to the warmer places to the cooler places, was a way for Country to rejuvenate. You left it there for next season so you could do it all again. We’ve got to allow Country to heal. We don’t do that anymore. What we’re doing is destroying and drying up the land even more, which is causing more bushfires, less rain and no water.”

Can you tell us anymore about the bush foods book you’ve been working on?

“I’ve had this little book for the last five to six years that has all my recipes and all my information I’ve been sharing with people. I’m very lucky to be able to work with my people, with our communities and have a yarn. When we get together, bush food is the ultimate – better than a lamb roast. It’s a way for us to reconnect, for us to get together and talk and be together as a family group. Food’s always an event.”

Jody Orcher was interviewed by food writer Lee Tran Lam from Diversity In Food Media. Diversity In Food Media is run by a collective of Australian journalists, and aims to promote and support under-represented voices in food media.