Can love conquer all? It’s a pertinent question given that Julia Kay, one half of Great Wrap, admits she and her husband, Jordy, identified as commitment-phobes just a few years ago. The pair met at a rooftop bar in Melbourne’s Fitzroy in 2019. Three months later, they registered their business name and in 2020 they launched Great Wrap, a material sciences company that turns potato waste into compostable stretch wrap. “We also got married,” Julia adds with a laugh. “It’s all been fairly quick.”

Julia, an architect, and Jordy, a winemaker, have always shared a biophilic attachment to the outdoors, each approaching their work as an extension of the environment. “I always liked wine because, for me, it was the creative expression of nature,” says Jordy. At 18, he travelled to Austria to work on a biodynamic farm. “That was where that passion and curiosity grew a lot more for sustainability, because it was not only the way you farm but how you treat those soils for generations that can have a really profound impact on the environment,” he says. For Julia, the tug of war she felt between the buildings she was working on and her eco ideals had her questioning her career. “You get into design thinking you’ve got the potential to design a future world,” she says. “Actually, in some projects, it can feel like a disruptive process [when] it should be restorative.”

The Kays began to look for a problem that was big enough that they could make a real difference. Each time Jordy shipped wines overseas or Julia sourced sustainable timbers, the products were packaged in petroleum-based plastic pallet wrap. “We saw that it was the connector of all business. The phone in my hand, the clothes I’m wearing — they’ve all been on a pallet at some point in their journey to be a consumer product,” says Julia. “We realised that if we could change that one material alone, the impact we could have on plastic waste could be quite profound and fairly massive.”

The product itself had to perform like standard pallet wrap, but its disposal formed a critical part of the equation, too. “Things can fall out of recycling loops and end up in our oceans,” says Julia, “so if you’re making material from nature that can completely return to the earth, for us that’s the solution.”

To test the market, the couple imported a maize-based waste product from China and posted about it on social media. They sold out in 24 hours, generating interest from wineries and airports around the globe. Now, in addition to their new manufacturing facility in Tullamarine, they are developing a biorefinery that will convert an estimated 50,000 tonnes of potato waste into compostable and marine-biodegradable Great Wrap, localising the entire process.

To create the product, the company extracts starch from potato waste (chip off-cuts) and subjects it to a polymerisation process before it’s stretched into Great Wrap. Jordy likens its production to making wine. “Making natural polymers is very much the same: figuring out how you’re going to process huge amounts of potato waste and how you’re going to ferment that and dispose of water and things like that, then make a product that is perfect and that people want to buy,” he says.

How do two outsiders disrupt an unfamiliar space? A cocktail of naivety and ambition. “At the start, it wasn’t like, ‘Oh, let’s change the paradigm of packaging,’ ” says Jordy, although, three years in, the company has set its sights on being the world’s largest pallet wrap producer and is working on sourcing other carbon feedstocks (raw or nature-derived materials) to convert into wrap. For the Kays, redirecting waste products into polymers is a promising start, but they’re now researching workarounds for Great Wrap’s after life, including recycling it into styrofoam and insulated panels. For that, they’ve recruited help from Monash University, with students involved in the research and development teams.

Inexperience is the couple’s wildcard: “I’ve learned that if you can muster up enough confidence to ask the question, more often than not people want to help,” says Julia, who has applied this lesson to new hires. Passion, patience and problem-solving trump qualifications. “Our head of sales is a videographer, our head of marketing is not from a marketing background,” she says. “If you can see the spark in someone’s eye, they’ve got a chance at Great Wrap.”

Perhaps as a result of being launched in a pandemic, the Kays’ business is hardwired to pivot. When the world shut down, Great Wrap shifted from commercial wrap to cling wrap for the kitchen, spying an opportunity in all those newly minted home cooks — and their leftovers. “We actually found the timing was really quite good,” says Julia, who notes the take-up was more diverse than anticipated. “I’ve been really surprised to see our consumer demographics,” she explains. “They’re not people you would immediately think would be attracted to our brand. They can be older, they’re often regional, so it’s really cool to see that people don’t have a resistance to making a better choice.”

Great Wrap has received investment from many corners of the world, including Thailand and Singapore, and the company launched in the United States in August. While the product is resonating worldwide, Julia finds the nuances of the various markets especially interesting, noting Thailand’s agricultural ties to waste versus America’s “culture of convenience”. The excitement of the founders is palpable, however Jordy admits it masks trepidation and lingering concerns. “Probably the biggest that gives me butterflies in my stomach is that market expectations in the US are far higher,” he says. “People expect to order something and have it at their doorstep within two days.”

The backing of impact investors who are conversant with their mission, including Simon Griffiths of the eco-friendly toilet paper company Who Gives a Crap, has been instrumental as Great Wrap expands. “I don’t think a lot of startups get that early on — the dos and don’ts. Having someone to call you out when you’re doing something wrong is so, so helpful,” says Jordy. Julia adds: “We have to do all our impact reporting and measure those metrics [for investors] and that’s really amazing to see.” Both offer the same advice for first-time founders: find the balance between feedback and backing yourself. Be adamant but agile. And what does that look like when you’re juggling marriage and a business? “We’ve just learned so much about each other as people,” says Julia, “which has helped us understand our relationship, too.”

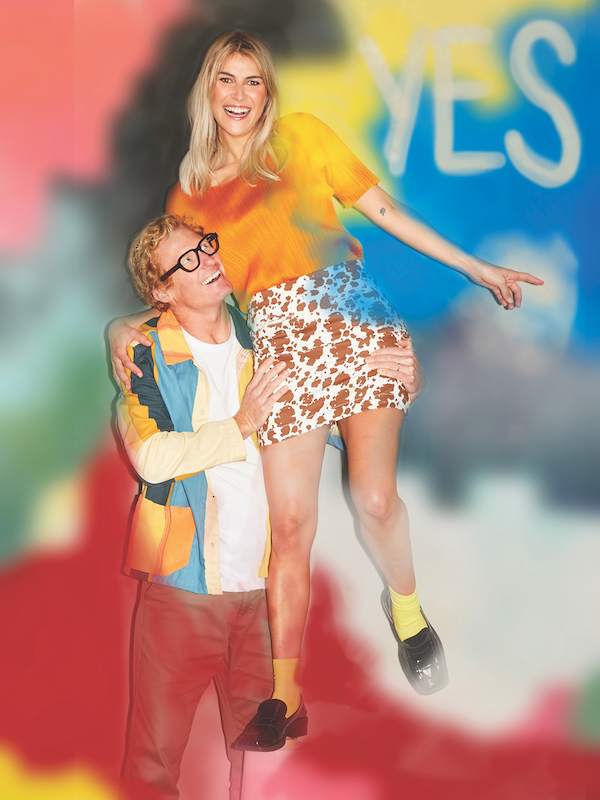

Great Wrap's Julia and Jordy Kay. Artwork by T Australia cover artist Vincent Fantauzzo.

Great Wrap's Julia and Jordy Kay. Artwork by T Australia cover artist Vincent Fantauzzo.