In his 1869 poetic novel, “Les Chants de Maldoror,” the French writer Isidore Lucien Ducasse, known pseudonymously as the Comte de Lautréamont, describes a young boy who is as “beautiful as the chance encounter of a sewing machine and an umbrella on an operating table.” Lautréamont’s book was rediscovered and championed by the Surrealists after World War I, and this particular simile became a kind of foundational mantra for the movement. Its juxtaposition of mundane objects in an unexpected setting conveyed the Surrealists’ cheekiness, their love of the incongruous and irrational and their overriding fascination with found curiosities.

The Surrealists were, as we would put it today, obsessed with the totemic power of the object and its ability to re-enchant humdrum reality: Marcel Duchamp’s punning readymades and Hans Bellmer’s fetishistic dolls, Salvador Dalí’s winkingly evocative lobster phone and Méret Oppenheim’s more overtly suggestive furry teacup. Members of the movement roamed flea markets in search of treasures and documented the bizarre wonders that floated into their subconscious while they slept. On the occasion of the landmark “Surrealist Exhibition of Objects,” held in Paris in May 1936, André Breton, the godfather of the movement, wrote an essay in which he called for the “total revolution of the object” — a goal the Surrealists arguably achieved, as numerous artists, from Louise Bourgeois to Sarah Lucas, have been influenced by their sensibility, images and ideas.

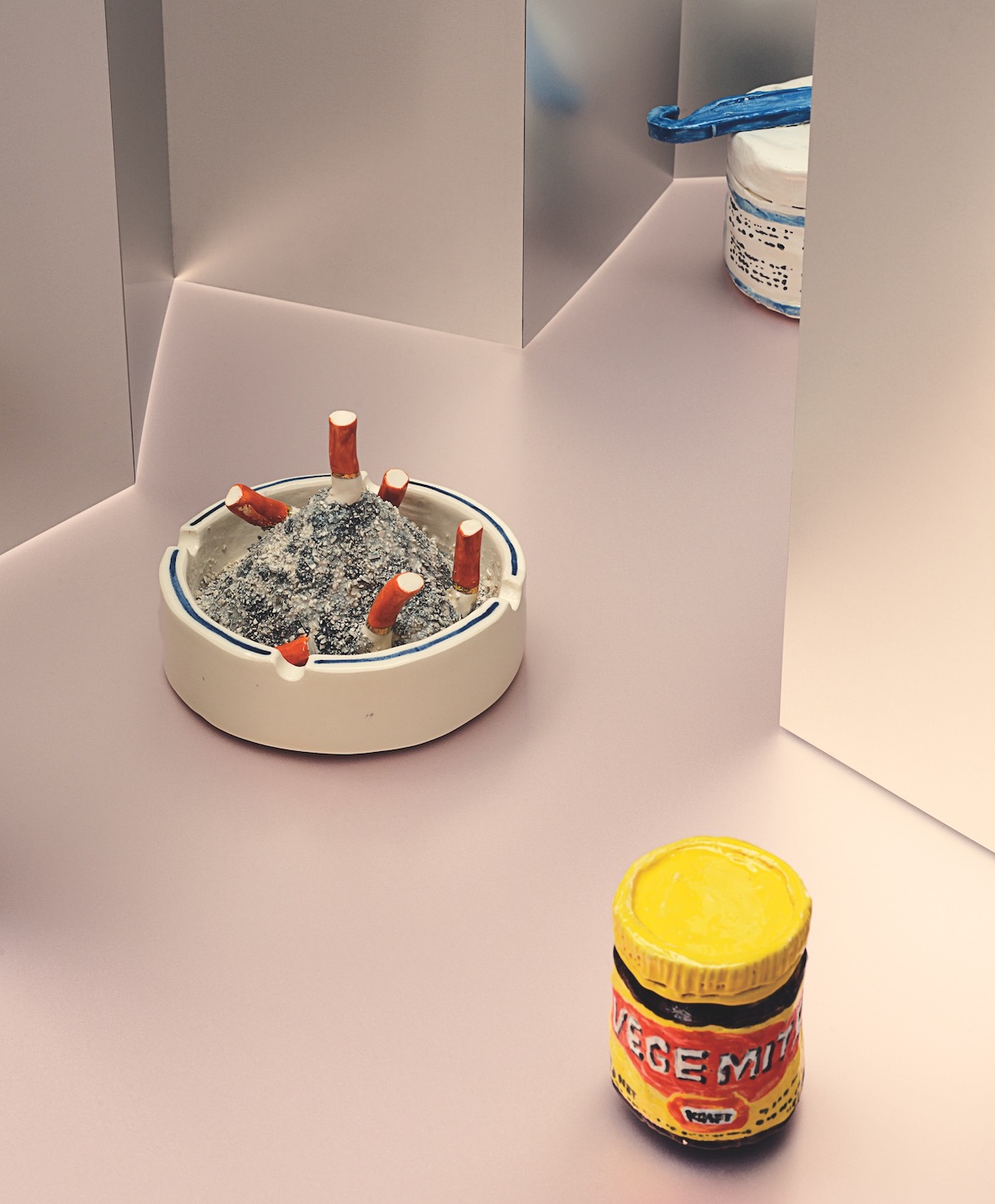

Nowadays, a group of contemporary artists are making what one might call oddity ceramics: playful, imaginative, funny but often slightly menacing objets d’art. Genesis Belanger, Rose Eken, Alma Berrow and Katy Stubbs are all working in a similar vein (as are a handful of notable others, such as Lindsey Mendick, Jessica Stoller and Woody De Othello). These four artists — all of them, not incidentally, women — take the notion of the readymade and subvert it, refashioning quotidian artifacts (cigarettes, sandwiches, shoes, lipstick, beer cans, sweaty plates of meat or eggs) in ceramics, a medium that was once considered a lowly craft but, in recent years, has been welcomed to the loftier echelon of fine art. Although their humorous, sometimes dark sculptures all share a spiritual DNA, each artist treats the object in her own highly specific, idiosyncratic way, which is perhaps not surprising, given the strange, often diminutive but eerily compelling works they’re creating.

The Brooklyn-based artist Belanger, 43, who sculpts pastel-coloured ceramics out of porcelain and stoneware, calls her work “Pop Bauhaus with a Surrealist bent.” Belanger worked for several years as a prop stylist’s assistant on campaigns for major brands like Tiffany & Co., Chanel and Victoria’s Secret, and finds inspiration in vintage advertisements — particularly in their use of beauty to induce desire: “It’s borderline offensive to actually offensive when you look at it now with our contemporary eye,” she says. Her unglazed matte clay objects, which she tints with powdered pigments in nostalgic confectionary hues the colours of Jordan almonds, tend to anthropomorphise everyday household articles. A thick, pink tongue extends from a tape dispenser. A foot-long hot dog is tucked into a platform sandal (get it?). Lamps have lips or breasts or arms and wear jewelry. These pieces are beautiful on the surface but rather disquieting beneath, recalling the creepily seductive work of Alina Szapocznikow, Robert Gober and David Lynch, as well as Man Ray’s iconic fashion images of feet, hands and Lee Miller’s tearful eyes.

Despite their seemingly decorative nature, Belanger’s ceramics aren’t stand-alone curiosities; they tell a larger story — as do the creations of all these artists. Belanger makes installations that conjure an entire mise-en-scène, building the furniture and wiring the lighting herself. “I normally start with what the room is going to be, and then build all the objects to tell a more fleshed out story,” she says.

The Danish artist Eken, 45, explores in-between spaces. While a teenager in Copenhagen, Eken worked as a stage technician for various punk venues, and this period of her life continues to inform her work. “When the audience is not there, when there’s nobody on the stage . . . these spaces are kind of suspended in time,” says Eken. “I’m intrigued by this moment just before something, or just after.” She’s created several “aftermath” installations, as she calls them, in which she reproduces the detritus left in theatres and concert venues in ceramics that are just slightly off in scale: cigarette butts, soda cans, beer bottles, plastic cups, lighters, band T-shirts, electric cables — commonplace items where private and collective memories meet. The viewer is left to impose their subjective narrative on the work: That was the night you got drunk; that was the show where you sneaked backstage. “We have a lot of ideas, subconsciously, about what these objects mean to us,” Eken says. We derive memories, identity, meaning from the sea of stuff in which we swim.

The London-based Berrow, a 29-year-old British ceramic artist who sells her pieces on Instagram, works in a similar vein, though on a smaller scale. She’s best known for her signature ashtrays that contain stubbed-out cigarettes, along with whatever else one might toss in during the course of an evening — lemon wedges, pistachio shells, spent matches, a steeped tea bag, clementine peels, a gold tooth. “It’s almost like doing a portrait,” she says of her ashtray worlds, which can tell the story of a life — for one couple’s commission she made a smoked joint, an apartment key and a scribbled note of affection — or simply a big night out.

Berrow took up ceramics in early 2020 while on lockdown at her mother’s house in Dorset; her mother, Miranda, is also a ceramist, so Berrow availed herself of her earthenware, kiln and high-sheen glazes. Berrow makes cigarettes, she explains, because she’s drawn to things that are “caricatures of themselves.” She’s also done oysters, lobsters, prawns, Ritz crackers, pomegranates, a backgammon board — all vaguely retro, often glamorous relics that carry cultural symbolism or baggage. But the common denominator is whatever Berrow finds comical. “A prawn cocktail, for me, is funny,” she says. “I don’t know why, but I find them hysterical.”

The British South African artist Stubbs, 29, also finds humor in unexpected places. “I like to explore the really dark side of human nature,” she says, “but to make it light.” Stubbs, who studied illustration at the School of Visual Arts in New York and now lives in London, makes bright, whimsical, cartoonish work — her palette includes a lot of superhero red, yellow and green — of unexpected oddities: large bowls of spaghetti and clams, a mountainous tower of crayfish and enormous round plates of meat (“disgusting and glossy,” she calls them), a nod to the Swiss artist duo Peter Fischli and David Weiss. Raised on the gothic stories of Edward Gorey and Roald Dahl, Stubbs is interested in gluttony and excess — “this human quality of ours,” she tells me, “where we want more and we want a big pile.” She’s fascinated by humans indulging their baser, more callous instincts, and much of her work tells that tale in some form. “I did one pot about a man kicking another man,” she deadpans. “Sometimes you just feel like kicking somebody.”

It made me think: Is the sudden proliferation of oddity ceramics, which I had previously chalked up to any number of art-world factors — a return to figuration, a renewed interest in traditional crafts, a long overdue focus on female artists — in fact a response to the ongoing darkness of this moment? After all, the original Surrealist movement, with its urge to systematically derange the senses, occurred in the wake of the First World War and its horrors. These are humorous, superficially light pieces — distractions — that also convey a wry awareness of an omnipresent and unsettling strangeness. What’s known and functional has been rendered impractical and pointless, which is fascinating but also kind of scary. As the author Anne Boyer writes in 2019’s “The Undying,” “Enchantment exists when things are themselves and not their uses.” These objects reflect back at us a world that both is and is no longer familiar.

From left: Genesis Belanger, “Untitled,” 2019, stoneware, porcelain, unique, courtesy of the artist and Perrotin; Katy Stubbs, “Prawn Cocktail,” 2019, earthenware and glaze, collection of Sarah Stengel, New York, courtesy of the artist and Paterson Zevi.

From left: Genesis Belanger, “Untitled,” 2019, stoneware, porcelain, unique, courtesy of the artist and Perrotin; Katy Stubbs, “Prawn Cocktail,” 2019, earthenware and glaze, collection of Sarah Stengel, New York, courtesy of the artist and Paterson Zevi.