Geeveston, an old logging town in southern Tasmania’s Huon Valley, is an unexpected location for a ryokan-style bed and breakfast. Even more surprising, on arrival at 155-year-old heritage-listed Cambridge House, is the discovery that my companion and I are the only guests.

It’s by design, says Thana Yazawa, who runs the “restaurant with rooms” with her husband, Kazumasa “Kaz” Yazawa. When they moved into the Victorian-era property in November 2021, they were booking 10 guests across the five bedrooms, Thana says. But it was too much for a two-person team. “We’re not here for the numbers. We’re here to deliver a relaxing experience,” she says. “People come from the UK, from Hong Kong, just to be with us. We want to recharge together.”

The Yazawas bought the house sight unseen from their home in Jakarta in 2020. Thana is originally from Thailand, by way of boarding school in rural France; Kaz moved from Japan to Australia in his early 20s, training under the Japanese-born Australian chef Tetsuya Wakuda in Sydney before joining the hotel restaurant circuit. His previous project was the opulent OKU restaurant and bar at Hotel Indonesia Kempinski Jakarta.

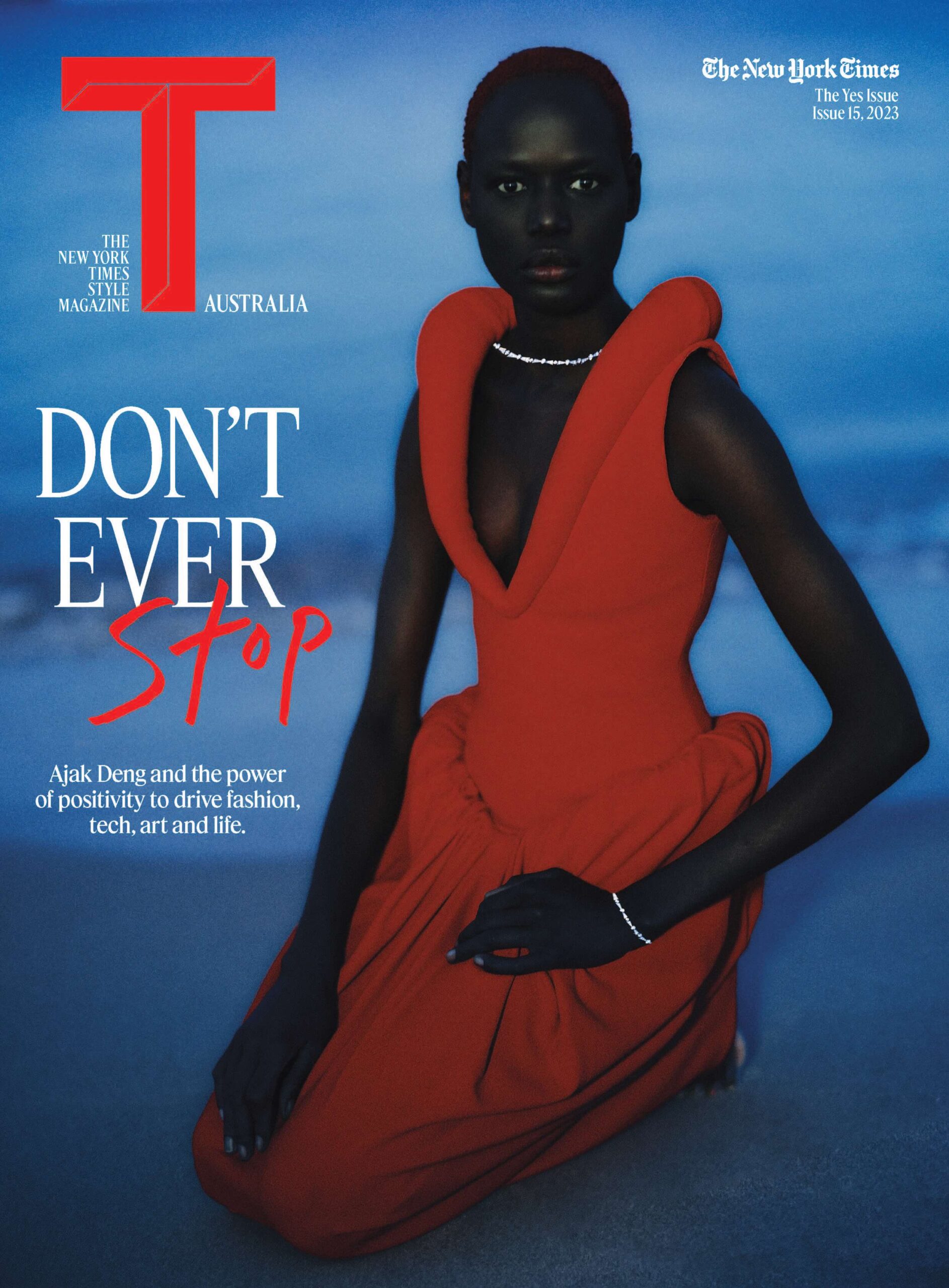

Bluefin tuna sashimi on buckwheat “pizza”. Photograph courtesy of Cambridge House.

Subscribe

Want more T Australia? Subscribe to the magazine and receive a bonus issue

ustralian international borders to reopen post Covid-19 allowed time for renovations. The floral wallpaper came straight down, and there was plenty of clutter that Thana was happy to see the back of. “I wanted a clean luxury,” she says. “Everything has to have a function.”

We stay in the Ume Room, one of five guest rooms all named after Japanese produce (Ume references the Japanese plum). The bedroom door is affixed with a “Geeves” sign that Thana says was inherited from the previous ownership and retained in honour of John Geeves, the English settler who built the house around 1870 on more than half an acre of land bordering the Kermandie River.

There is a queen bed, an antique dresser and an olive-green chaise lounge, complemented by Japanese calligraphy and cut flowers in minimalist stone vases. The ensuite is more 1990s than 1870s, but features a claw-foot tub and a custom-designed 13-step skincare collection inspired by shinrin-yoku, the Japanese practice of forest bathing.

We spend the last of the afternoon roaming the slightly wild cottage garden, which extends to the river. Three platypuses live here, Thana says, pointing out their burrows. Despite multiple dashes to the water’s edge, the notoriously shy creatures remain elusive.

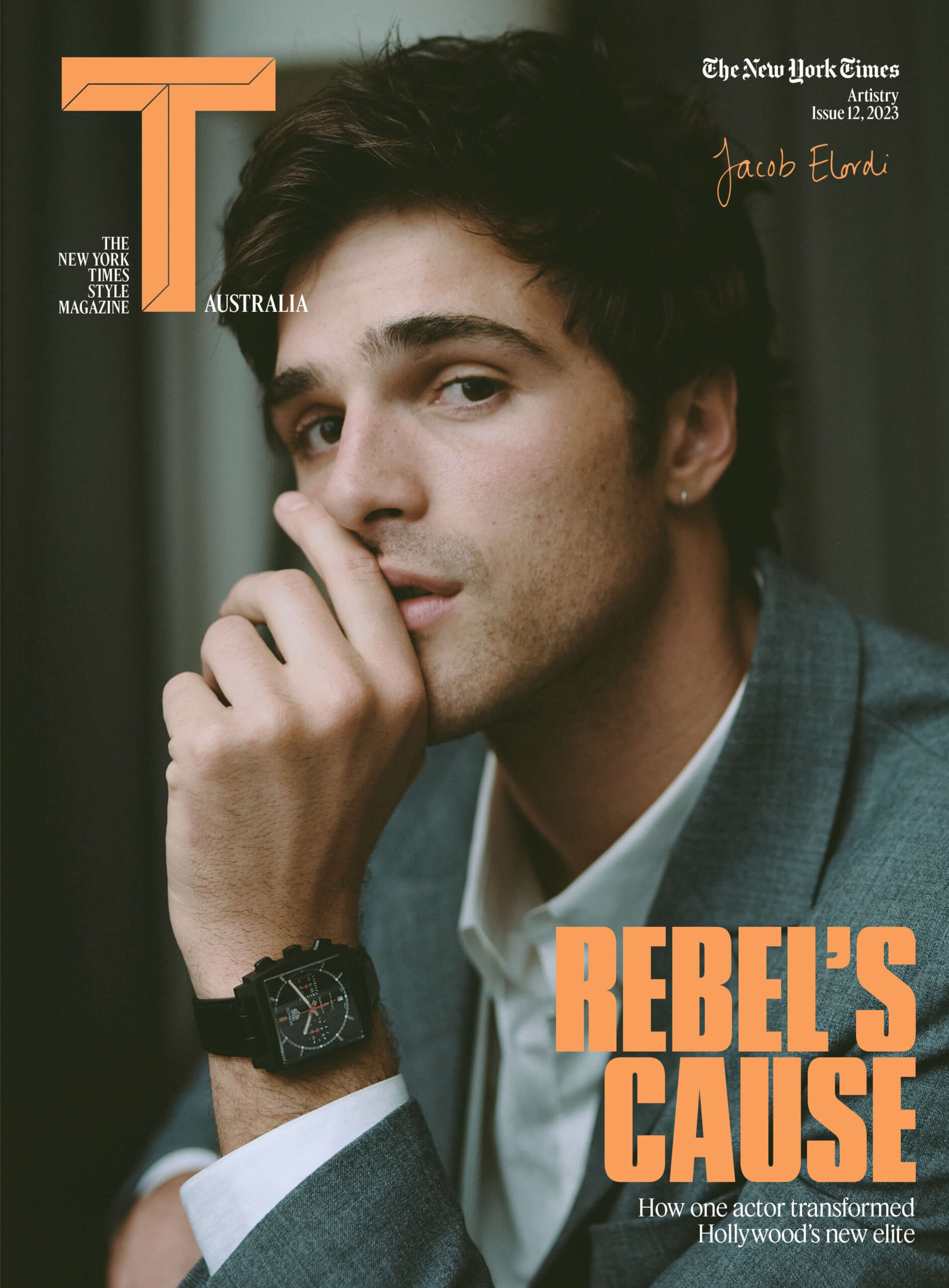

A choice of sakes to complement the seafood-driven menu.

At 6pm, Thana throws open the door to the dining room. By the window, a table for two is set with white linen, Huon pine placemats and spindle-thin chopsticks crafted from the rare Oya stone, which are exclusively made in the Oya district of the Japanese city of Utsunomiya.

In the centre of the room is a 1.5-metre-long butcher’s block laid with bluefin tuna, sea urchin, freshwater eel, scallops, baby octopus, abalone and venison — all sourced from local fishers and hunters. As far as room reveals go, this is up there.

Stationed behind the butcher’s block, which was custom-made to suit the traditional Japanese cutting position, chef Kaz, wearing a chef’s jacket, jeans and Blundstone boots, stokes the open fire over which he will prepare this evening’s 14-course menu. This is not an optional extra. Each night’s stay includes either the full omakase experience or a shorter (but still generous) four-course Western-leaning menu on request, afternoon snacks and a traditional Japanese breakfast.

“What you’re trying now is plum wine I make with Japanese plum from Cygnet [a nearby town]. Just one gentleman grows it,” says Kaz as he ladles a syrupy, amber-coloured liquid from a large Kilner jar affixed with a Hibiki label (a nod to its base spirit, Japanese whisky) into our waiting cocktail glasses.

Thana explains that they don’t pitch their cuisine as “Japanese food”, despite the use of Japanese techniques. “We want you to feel the land and the place of where you are now,” she says.

The first plate is sashimi prepared in a “pizza style”, Kaz says, delivering a crisp buckwheat cracker spread with a creamy yuzu, seaweed, shiitake and soy sauce-infused relish and topped with wafer-thin slivers of aged bluefin tuna. A baton of fire-licked sourdough follows, dripping with butter and topped with raw urchin. “In Japan, this would be on sushi rice. But this is the local way,” Kaz says.

As Kaz assembles a parade of tiny seafood dishes, Thana keeps our Tokyo-made Kimura glasses topped up with sake, one of the few imported consumables on offer. The thinnest drinking glass in the world, it too was selected for its experiential properties. “You should feel the fluid pass your lips without feeling the container,” Thana says, as I try not to crush the glass just by looking at it. “Different cups, different experiences.”

In theory, Cambridge House’s menu changes seasonally, but that depends on who is staying. Almost everyone who visits returns, says Kaz, who sees it as a personal challenge never to serve someone the same meal twice. Given the effervescent energy the Yazawas infuse into the proceedings, it’s clear that it’s not only the food that brings people back. “We don’t say ‘tourists’ here,” Thana says. “You are dinner guests who stay over.”

Despite having sworn just 10 hours earlier that I’d never eat again, the next morning I’m lured into a pre-departure breakfast. “Would you like us to keep the noise low?” Thana asks, which is probably a gentle way of asking if we’re hungover. We are, a little, but it’s a problem solved by fluffy white rice, steaming miso soup, asparagus in dashi jelly, carrots poached in mirin and sweet sake, tender broccoli in sesame dressing and purple pumpkin korokke (the Japanese take on French croquettes).

Here in the Huon, far from the bright lights of Jakarta, luxury doesn’t mean edible gold leaf or sterile silver service. Sometimes, luxury is as simple as a Japanese-style egg sandwich with the crusts cut off.