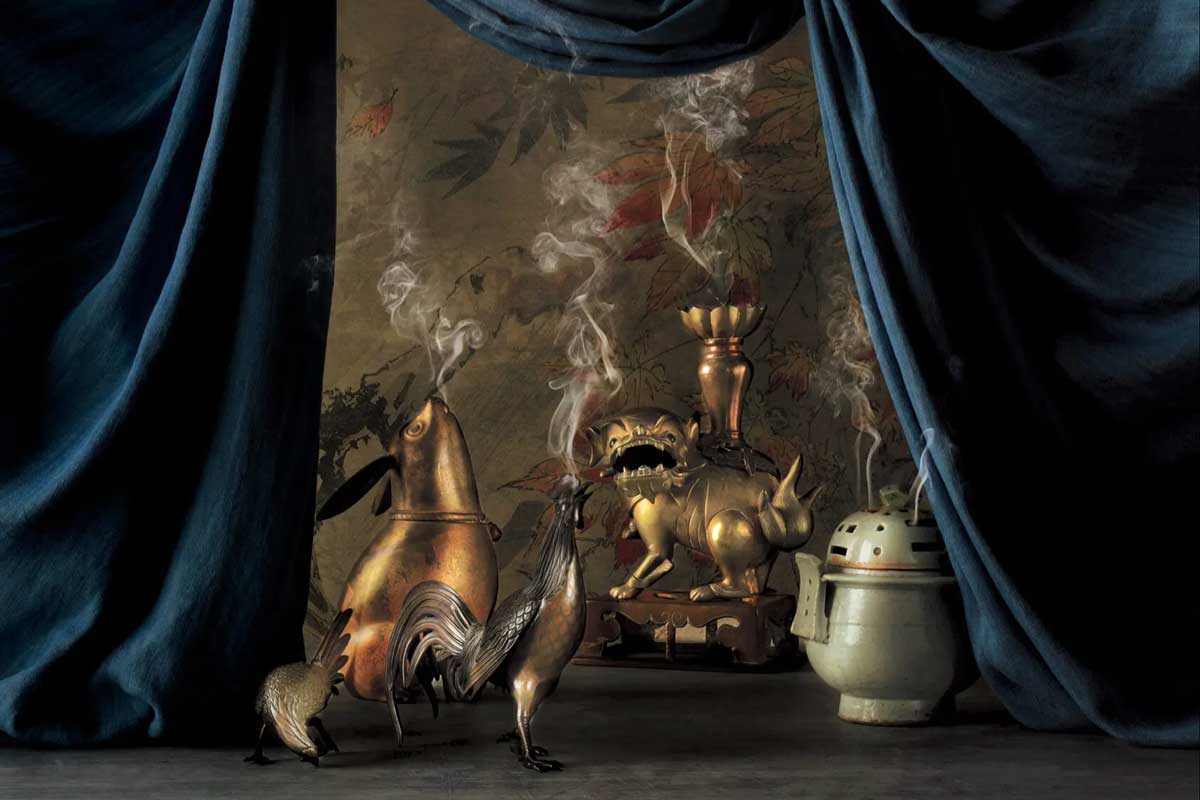

In Ancient China, time was measured in spirals of smoke, from incense burning through the night. So time had a scent, of warm, sweet sandalwood, cooling camphor, cypress with its evergreen kiss — and under it all, a char on the air, a memory of something set on fire. A clock could be as simple as a fistful of joss sticks, although more complex versions were engineered over the centuries: trails of fragrant powder smouldering in circular mazes, following a twisting path from noon to noon; incense sticks placed under strings tied with tiny weights that fell and clanged against a metal plate at intervals as the strings burned through.

Scent is a paradox, sensual yet intangible, a physical presence without a physical form. It can be intimate and half-hidden, a discreet daub at the wrists, a faint pulse when a stranger walks by. But in the beginning, it was fire — the word “perfume” can be traced back to the Latin per fumare, “through smoke” — and a summons to the gods. Five millenniums ago, the Mesopotamians lit incense at altars as a temple offering, coaxing fragrance out of the sap and shavings of cedar, juniper and cypress. In the golden age of Greece, in the fifth and fourth centuries BC, such “sacrificial aromas” were considered kin, in their disembodiment, “to the divinities they were intended to attract”, writes the British classicist Ashley Clements in his 2014 essay “Divine Scents and Presence”. Early Christians spurned incense as pagan excess, but in the fourth century AD, when the once persecuted believers earned legal recognition and could profess their faith openly, scented smoke started to infiltrate churches, musky clouds of frankincense stirred up by the swinging of a censer down the aisles, like a pendulum.

None of this was metaphor. Incense was a practical tool, weapon and medicine at once, wielded to banish foul smells and with them disease and evil spirits, from pre-Columbian Mesoamerica to medieval Europe to the Himalayas. According to a Sanskrit text that may have been written as early as the first century BC, the dharma, or the nature of reality, could be taught without sound or language, through perfume, whose nebulousness required supernal focus — the kind necessary to comprehend the universe. In 15th- century Japan, this idea of fragrance as a cerebral trigger was formalised in the ceremony of koh-do as “listening to incense” (mon-koh), in which rare wood was laid on a burner over charcoal and practitioners bowed their heads to take in the scent, trying to call it by name.

There are fewer scents in our lives now, and fewer opportunities to learn them. As the American philosophy scholar Larry Shiner writes in “Art Scents: Exploring the Aesthetics of Smell and the Olfactory Arts” (2020), advances in science in the 1860s and 1870s revealed that odours were neither the cause nor cure of sickness. After that, we began to resist powerful scents, as if resisting our more primitive, animal selves. In increasingly crowded cities, we demanded sanitised spaces, offices that banned perfume, free of any troubling aroma that might betray our proximity to others, how closely we’re all packed in. We chose to live in a cleaner, emptier world.

Yet sales of incense have risen during the Covid-19 pandemic, even as — or perhaps because — many temporarily lost their sense of smell to the virus (with some having yet to regain it), making it abruptly precious. The desire to perfume the air we breathe might seem like a return to superstition, hoping to keep death at bay; but for those in quarantine, confined at home, incense offers a kind of escape, opening up increasingly claustrophobic spaces and rendering them, if only for a moment, beautifully unfamiliar.

The incense of today bears little resemblance to the New Age accessories of the 1970s or the perpetual fog of patchouli on university campuses. Now there’s an emphasis on natural ingredients and Old World craftsmanship sustained over time — as well as proper compensation for it, via fair-trade producers, as with the dark, rugged sticks of Breu resin from the Amazon rainforest, imported by Incausa Australia from the owner’s home country of Brazil, and twisty ropes of incense rolled by hand in Nepal, sold by Catherine Rising of Rochester, New York. The delicate incense sticks of the Parisian house Astier de Villatte are made on the Japanese island of Awaji, in the way that artisans there have made them for generations, from resins, woods and herbs crushed into paste, kneaded and left to rest until the scent ripens, then cut and dried in the western winds that sweep off the ocean.

Modern incarnations, less bound to history, are explicitly posed as design objects. The incense cones of Blackbird in Seattle are monoliths in miniature — eerily symmetrical and uniformly black, whatever their fragrance (among the selections is the vaguely hungover scent of whisky and cigarettes after a bleary night). Cinnamon Projects packs its skinny sticks in black- corked vials and boxes stamped with gold foil; you’re meant to prop them up in lustrous concave burners or lean blocks of brass designed with nowhere to catch the ash. The online description is crisp: “The ash falls where it may.”

The scents tend to be more subtle than their historical counterparts, as with Na Nin’s lucid yet barely there sea air and dune grasses, or intimations of carnal oud and sunny bergamot from Tennen in Phoenix, fragrances in watercolour. But the most minimalist gesture, from Santa Maria Novella in Florence borrows from an old Armenian custom: pieces of paper no bigger than a strip of chewing gum. Take one and fold it accordion-style so it can stand on end, then strike a match and hold a corner. As soon as the flame catches, blow it out.

What is left is a smouldering, the smoke peeling off and vanishing as the paper blackens and crumbles, giving off the scent of frankincense and myrrh, ancient libraries and the heaviness of honey, and chased by a slur of orange-red, the last bit of glowing. It spends itself so quickly; it’s not meant to survive more than five minutes. You can watch it to the bitter end and think, “That was time. I, too, will crumble.”