Yigit Turham, the Milan-based director of branding and entertainment relations at Valentino, was in Los Angeles last year when he first heard about the infamous book stylist. Rumour had it that celebrities and fashion influencers were paying someone to select reading material for them to carry in public. (Whether they read it was another thing, and, to echo a sentiment shared by a pair of withering college-student characters on the HBO satire “The White Lotus” (2021), beside the point.) In paparazzi photos or on their own social media accounts, these props, because that’s essentially what they were, communicated something far more powerful than a press statement ever could. Today, when entertainers are required to have an immediate, uncontroversial and neatly packaged response to every newsworthy occurrence — when their personal brand is expected to, as Walt Whitman once wrote, contain multitudes — a picture of a book is worth a thousand words. But when Turhan asked for the name of this mysterious figure, his contacts got cagey. “They acted like they had never heard of such a thing, as if we hadn’t just discussed it,” he recalls.

Turhan’s curiosity made sense: a literary sensibility has been central to the mission at Valentino since 2018, when the label’s creative director, Pierpaolo Piccioli, invited the poet Rupi Kaur to read at a party following a runway show in Japan. Last year, the Italian fashion house partnered with Belletrist, a social media community of readers run by the creative consultant Karah Preiss and the actress Emma Roberts, on the first in a series of text-based advertising campaigns called “The Narratives”. (The idea came to Piccioli, a bookworm himself, after he was given a copy of Donna Tartt’s 2013 novel, “The Goldfinch”, in which a character is described as being “all Valentino-ed up”.)

The second instalment of the promotional series, which came out in March on World Poetry Day, focused on the theme of love, and featured colourful contributions by 17 writers including Douglas Coupland, Michael Cunningham and Emily Ratajkowski. When Turhan was later told that Preiss herself might be, if not the book stylist, then at least a book stylist, he called her. “ ‘Look, you must tell me if it’s you,’ ” he remembers saying to her. “She started laughing, and then she replied, ‘Honey, I can neither confirm nor deny.’ ”

It’s a sunny Friday in the middle of March, and Preiss has just returned from Atlanta, where she visited the set of “Tell Me Lies”, a relationship drama adapted from Carola Lovering’s novel of the same name, which she and Roberts are executive producing. (They’ve also been working on “First Kill”, a vampire series based on a short story by V E Schwab, which finished shooting last year and is now on Netflix.) On the patio of a coffee shop in New York’s West Village, in a light nylon jacket with pockets big enough to fit a paperback, Preiss recalls a conversation she had with Roberts, her best friend since they were teenagers, and the writer Ariel Levy. “Emma said, ‘I want to do for books what Kylie Jenner did for lip kits.’ Ariel was like, ‘What does that mean?’ And Emma said, ‘Well, that you have to have one.’ ”

Roberts’s statement calls to mind a scene from the 2006 film “The Devil Wears Prada”, in which Miranda Priestly, a fictional magazine editor inspired by Anna Wintour, demands that one of her assistants fetch the impossible: the unpublished and closely guarded manuscript of a forthcoming “Harry Potter” book. In the movie, the galley becomes the ultimate fashion item. Maybe in real life, too: in April, Belletrist and Valentino revealed a limited-edition hot pink Valentino box with three drawers lined in the label’s trademark red, each containing a book that hadn’t yet hit stores.

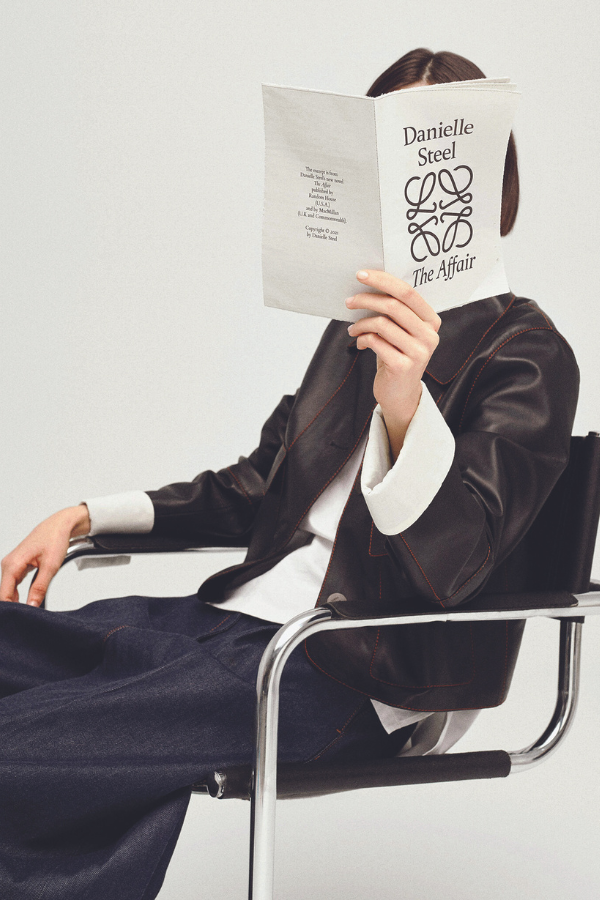

The worlds of literature and fashion have flirted with each other since long before Arthur Miller and Marilyn Monroe tied the knot in 1956, but in the past few years, books have become such coveted signifiers of taste and self-expression that the objects themselves are now status symbols. Although Valentino is certainly at the forefront of this scholarly style moment, it isn’t alone. For the past year, Chanel has been developing a robust literary program that includes a salon-style panel series and podcast hosted by the brand ambassador Charlotte Casiraghi. At Loewe, Jonathan Anderson included an excerpt from Danielle Steel’s novel “The Affair” (2021) with the show notes for his autumn 2021 collection. Etro issued a travel-size book published by Adelphi Edizioni (known for its Italian translations of classics by the likes of Milan Kundera and Friedrich Nietzsche) with the invite to its autumn 2022 menswear show, for which models walked through Bocconi University in Milan with a book in hand.

That same season, Jack McCollough and Lazaro Hernandez, the designers for Proenza Schouler, tapped the American author Ottessa Moshfegh to write a short story to accompany their collection presentation and Kim Jones debuted clothing for Dior Men inspired by Jack Kerouac’s “On the Road” (1957). The runway at that show was made to look like the unfurling scroll on which Kerouac typed the book’s first draft. “Designers have always looked to other forms of art for inspiration,” says Preiss. “What I do find interesting, though, is that publishing is happy to oblige. It’s sort of like the smart, quiet girl who gets attention in high school. Penguin Random House is ‘She’s All That’.”

Preiss, who was raised in New York, grew up knowing how hard it can be to get people to read. Her mother, Sandi Mendelson, runs Hilsinger-Mendelson, a literary public relations firm. Her father, Byron Preiss, who died in 2005, was a writer who started his own imprint, Byron Preiss Visual Publications, in 1974. That’s partly why she has no patience for the publishing industry’s elitism, much of it a poorly veiled expression of misogyny. “What’s the goal?” she asks. “Is it to take people down? You’re not going to get anywhere by making anyone feel stupid.” Hence, she doesn’t sniff at the idea of Kendall Jenner on a yacht with a sticky-noted edition of Chelsea Hodson’s essay collection “Tonight I’m Someone Else” (2018). And if Gigi Hadid wants to carry around a copy of Albert Camus’s “The Stranger” (1942) during Milan Fashion Week, why shouldn’t she? “I think if you spoke to any writer, they would prefer to have Kendall and Gigi reading their book than not,” says Preiss. “Those who argue that an influencer holding books is bad for books are stupid. A book doesn’t suddenly become cheap because someone reads it. Then there’s the snark of, ‘Are these people even reading books, or are they just taking pictures with them?’ As someone who loves to read, I truly don’t care. The alternative to pretending to read books is just not reading them and not telling anyone else about them.”

When the conversation turns to book styling, Preiss sighs. On an emotional level, she understands why some might find the idea objectionable: reading is one of the few things we’re still allowed to do alone, undisturbed and for ourselves, without an audience; for many, to perform that private act is to mock it. A book suggests interiority, which feels increasingly precious in an age of thirst traps, hot takes and humblebrags. But it’s shortsighted, Preiss thinks, not to mention disingenuous, to separate the reading of books from the selling of books — after all, publishing is a for-profit business, and one that can be quite lucrative. And isn’t book styling just another version of brand consulting or creative directing or even life coaching? “Just ask me,” she says. She has been waiting for the question. “Am I a book stylist? I am not. Or maybe I am, I don’t know. Would it be the worst thing in the world if I were?”

“It’s a great way for people to accessorise,” says Jenna Hipp, who, with her husband, Josh Spencer, puts together libraries for other people that can range in price from about $700 to almost $300,000. Spencer owns The Last Bookstore, set in a two-storey, 2,000-square-metre repurposed bank in downtown Los Angeles. (He also maintains two warehouses that between them contain more than a million books.) Spencer handles the curation of titles, handpicking them based on content and context, performing a service that has been around for centuries, and one that you can also get at stores such as Daunt Books and Heywood Hill in London and Strand in New York. But what The Last Bookstore has that the others don’t is Hipp herself, a mostly retired celebrity nail artist in her 40s whose primary concerns are aesthetic: colour coordination, shelf accessories and plants.

Since launching their library-building business at the beginning of 2021, she and Spencer have worked on social clubs, law and tech offices and a smattering of homes for Pacaso (a United States-based company that sells a share of residences to co-owners for occasional use). While the pair’s corporate clients are often given the opportunity to approve Spencer’s selections, or at least to sample stacks, they mostly opt to walk into a finished room without having weighed in. “They care more about how it looks than about the actual books,” Hipp says.

Their roughly 10 celebrity clients — Hipp prefers to protect their anonymity, but says, “You wouldn’t be surprised by who we work with if you went to my website and saw whose nails I’ve done” — usually begin the process by sending her a picture of an empty bookshelf in their living room or office, often along with a colour scheme or a mood board. Then Spencer combs through his inventory for tomes that reflect their stated criteria. “It could be art and architecture monographs in shades of peach, blue and green, or all leather-bound books for a room with a goth feel,” says Hipp. “Curated libraries have become very popular. Clients will say to us, ‘I want people to think I’m about this. I want people to think I’m about that.’ ”

Hipp came to book styling by accident. Although she has largely stepped away from doing nails, she used to show up at photo shoots with gifts in the form of essential oils and a book she thought one of her regulars — the actresses Emilia Clarke, Jennifer Garner and Jennifer Lawrence among them — might enjoy reading or displaying on their coffee tables. In time, she started getting requests: a few vintage books for a guest room, a first edition of “The Catcher in the Rye” (1951) as a last-minute birthday present. Early in the pandemic, the musician Alanis Morissette texted Hipp a list of her family members’ reading preferences and received in return a pile of new and used titles. (The Last Bookstore now sells “Book Bundles”, whereby someone receives $40 to $300 worth of books instead of enough to fill an entire shelf or room.)

On the second floor of The Last Bookstore, there’s a stack of shelves on which books have been organised by colour to conjure the spectrum of a rainbow. It’s not meant to be taken too seriously, but it’s also quite beautiful. “People are like, ‘How could you do that? That completely takes away from the integrity of the books,’ ” Hipp says about the decorative arrangement. “But books bring life in all forms. Whether they’re sitting on a shelf or being read, they bring something to the space. Their existence alone gives off an energy. As long as books are being appreciated in some way, I’m happy they’re there.” Does it not matter to Hipp, then, if her customers read the books she styles? “It doesn’t matter to me,” she says. And yet, if there is someone choosing books for celebrities to take photographs with, she swears it isn’t she: “Have I styled books for a greenroom? Yes. A red carpet? No.”

In any case, business at the shop appears to be booming. It takes work to navigate the crowds that have gathered to photograph the store’s striking Tunnel of Books, an immersive archway made from hardcover volumes and illuminated by LED strip lights. (“People come here just to take pictures,” Hipp says. “They couldn’t care less about the books, but it’s another way to get them in the door.”) Soon, there will be a display dedicated to Belletrist-approved titles by authors who will almost certainly benefit from the endorsement.

“If you ask any writer, they want to be read, but they also want to keep writing,” says Preiss. “The bottom line for publishers is not ‘Did your book get read?’ It’s ‘Did your book sell?’ And famous readers sell books. Now, if someone is getting paid to choose those books to make a famous person look a certain way, I guess there’s something a little sinister about that. But you know what? Somebody’s got to do it. Somebody has to read a book.” Just who that somebody is remains — like some of literature’s most haunting endings — a mystery.