Balenciaga, one of the most storied and controversial houses in fashion, has a new designer.

Last Monday, Kering, the group that owns the brand, announced that Pierpaolo Piccioli, the longtime head of Valentino who parted ways with that brand in 2024, had been named creative director, in charge of womenswear, menswear, accessories and couture. He replaces Demna, the mononymic designer who led Balenciaga since 2015, transforming it into a lightning rod for both trends and social issues, and who announced this year he was leaving to join Gucci (which is also owned by Kering).

The news puts Balenciaga into the hands of an experienced and beloved industry figure. The brand has struggled to regain the sizzle it had in the early years of Demna’s tenure after almost being canceled after allegations related to what some saw as a badly misconceived ad campaign.

And, at a moment when Kering is struggling after dismal 2024 results, with a 12 per cent fall in revenue and creative change at three of its brands (Bottega Veneta, Gucci and Balenciaga) it signals a potential shift in approach.

Piccioli, after all, is one of fashion’s great romantics, while Demna is one of its great disrupters; his vision is more utopian than dystopian. Piccioli is known for his couture rather than his elevated streetwear — a detail that Francesca Bellettini, Kering’s deputy CEO, cited as particularly important for Balenciaga in the news release about his appointment. And perhaps just as significantly, Piccioli has ambitions to change the very image of the industry.

“We are in a new moment of fashion,” Piccioli said in a call. “Before, there were founders. Then there was the phase of the creative director. This is the third phase. The human phase.”

It is a phase that will see more change in creative direction than has ever occurred in fashion, with more than15 fashion houses switching designers this year alone. Piccioli said his mission was to create a new template for how that can happen. So that it isn’t so much a game of musical chairs as “a passing of a torch.”

Piccioli, 57, called the decision to join Balenciaga a “natural” one and said his plan was not to wipe the slate clean, as many designers have done (following a template created most famously by Hedi Slimane). He wants to honour those who came before him. In the news announcement, he included a letter thanking every designer — Cristóbal Balenciaga, the founder; Nicolas Ghesquière, who put Balenciaga back on the fashion map; Alexander Wang, who managed the transition after Ghesquière left; and Demna — for their work.

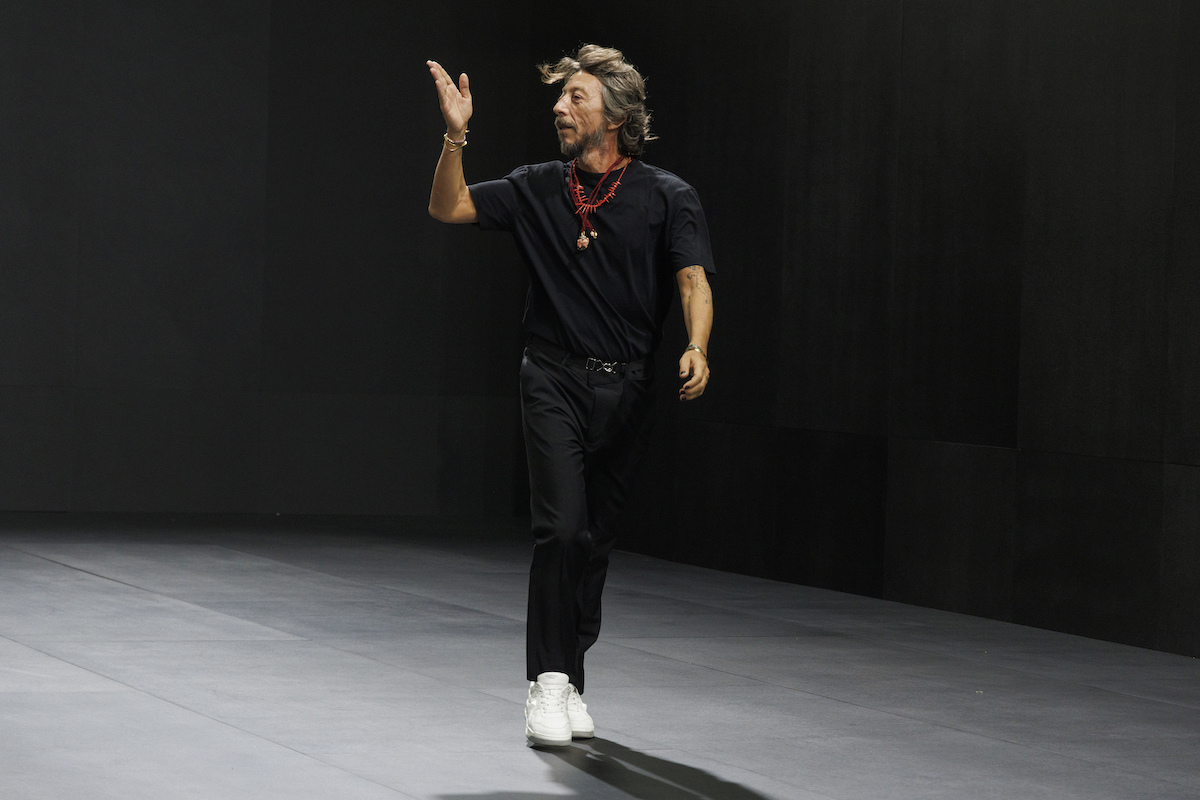

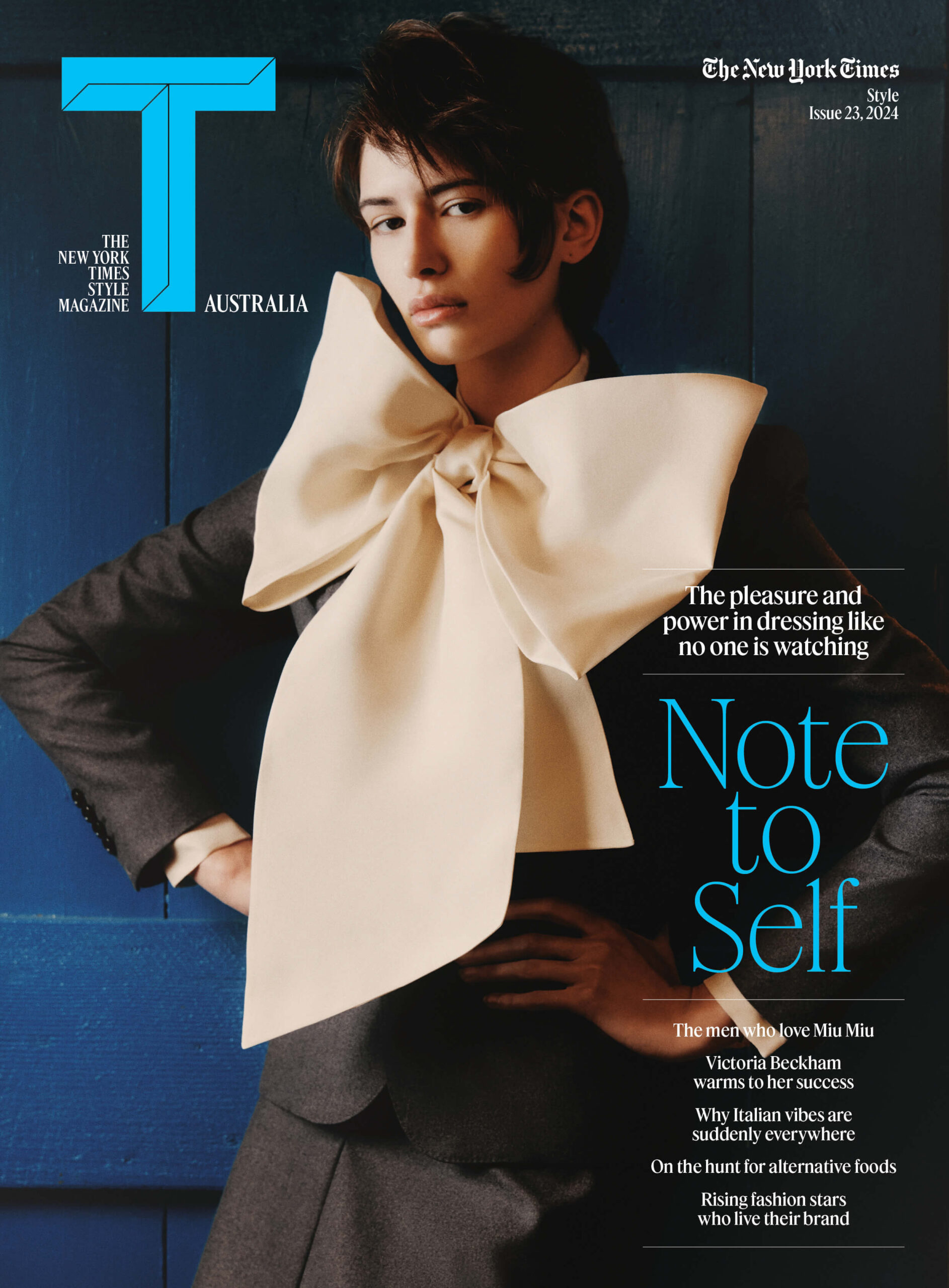

Pierpaolo Piccioli at the Valentino spring 2023 fashion show in Paris in October 2022. Photograph by Valerio Mezzanotti/The New York Times.

Subscribe

Want more T Australia? Subscribe to the magazine and receive a bonus issue

“I don’t want to deny the past,” Piccioli said, “but to embrace the past, to build a new future. I don’t want to cancel what has been, because a house is made by lots of people. This is a chance to change the rules from the inside, give a different image of fashion and of designers, of creative directors, because we respect each other.”

He and Demna have met and spoken multiple times, he said. (He has attended Demna’s Balenciaga couture shows.) There are no immediate plans to redo the stores or get rid of old inventory and replace it with his designs. Piccioli will be relocating to Paris from outside Rome, where he lives, and he and Demna will overlap for a month at Balenciaga before Demna officially leaves in July after his final couture show. Despite their apparent differences in style, they share a certain approach to fashion, Piccioli said.

“We are designers, not as curators,” he said. “In order to interpret a house, you have to get the spirit of the house, not just go back to the archives. We are called to witness our times, and our job is to give our vision of beauty relating to those times.”

While Piccioli was not as overtly political in his shows as Demna, who took on climate change, capitalism and the war in Ukraine, he has been unafraid to grapple with current events, especially as relating to diversity and inclusion.

His appreciation of couture stems not from a desire to focus on exclusivity, but because it represents “uniqueness and care,” the touch of the human hand in an age of artificial intelligence. (It is why he brought all of the seamstresses and tailors from his atelier out on the runway to take a bow after every show.) And he has long been inspired, he said, by the history of Balenciaga itself.

Though he said he didn’t believe in destiny, he did note that his first Instagram post, in 2018, was a picture of Cristóbal Balenciaga’s famous 1967 wedding dress, from the Met’s Costume Institute exhibition “Heavenly Bodies: Fashion and the Catholic Imagination.”

The dress has always been “one of my greatest inspirations in terms of volumes, shapes, innovation,” he said. “So I uploaded that picture with a quote from Brancusi that I really love: ‘Simplicity is complexity resolved.’”

What that means when it comes to clothes will be clear in October, when Piccioli will present his first show during the Paris ready-to-wear collections.

This article originally appeared in The New York Times.