Not long after he joined the Princeton University Art Museum in 2006, the curator Karl Kusserow wore a bracelet bearing the phrase “Stop global warming” to a staff meeting. His colleagues noticed (“It was,” he conceded, “kind of ugly and noticeable”), but only a few of them knew it referred to a cause. The term was just getting mainstream traction — this was the year Al Gore released “An Inconvenient Truth” and Vanity Fair launched its first Green issue. But the science suggesting that industrial societies have thrown climatic rhythms wildly out of whack had been around for decades. Just a year earlier, the environmentalist Bill McKibben had railed against the culture’s perceived indifference. “Where are the books? The poems? The plays? The goddamn operas?” he wrote in an op-ed for Grist. “Compare it to, say, the horror of AIDS … which has produced a staggering outpouring of art that, in turn, has had real political effect.” For future generations looking back on the present, “the single most significant item will doubtless be the sudden spiking temperature. But they’ll have a hell of a time figuring out what it meant to us.”

The art world has been making up for lost time in recent years, its overdue compensation crescendoing in the past six months, when more than a dozen exhibitions explicitly confronting climate change have been on view in cities from Santa Fe, New Mexico, to Singapore. What happened? Maybe it was the election of Donald Trump. Maybe it was the rise of extreme weather events in art world bastions — the flooding of downtown Manhattan in 2012 during Hurricane Sandy that had dealers bailing out their gallery basements, or the ongoing wildfires that have forced evacuations in Los Angeles. Whatever the reason, support for environmentally conscious art is surging. In December, the Helen Frankenthaler Foundation and Asia Society in New York announced a new series of $15,000 grants for emerging visual artists whose work “directly addresses the climate crisis.”

Yet more of anything is not necessarily good, especially not at a moment when unchecked production and conspicuous consumption spell planetary demise. As early as 2007, the Chicago-based curator and early supporter of environmental art Stephanie Smith cautioned that a glut of superficially righteous exhibitions could give hits of easy virtue to viewers and museums alike. “If sustainability or climate change become art trends du jour, we risk providing a palliative to ourselves and to our audiences without contributing much to artistic production, nuanced debate or lasting social change,” she wrote in the catalog accompanying “Weather Report: Art and Climate Change,” an early exhibition devoted to the topic organised by Lucy Lippard.

But alongside the inevitably facile attempts — paintings of burning forests, icebergs melting away in urban squares, clumps of dead sea grass pinned to gallery walls, alarmist works that function as little more than propaganda — something else has emerged: a new, sometimes inadvertent form of protest art, one that avoids agitprop and in that way subverts ideas of what protest art should do and can be. Consider the former library on a bluff overlooking Stykkishólmur, a small harbour town on the western coast of Iceland. Here stand 24 clear glass pillars of water, originally harvested from glaciers around the country. The three-metre cylinders, luminous in the mercurial light of the changing sky, stretch and blur the silhouettes of visitors as they move and the weather shifts. It is a place to melt and dissolve, an ode to constant flux. The American artist Roni Horn, who has made regular trips to Iceland since 1975, conceived of the project, “Vatnasafn/Library of Water” (2007-present), as a contemplative space and a community centre, a site for readings, residencies, chess games and reflections on weather. With collaborators, she collected weather stories from dozens of locals; visitors can add their own, creating what she calls “a collective self-portrait.” The library subtly conjures a future in which ice only exists in written accounts — already, one of the glaciers from which Horn collected water has vanished. But Horn didn’t intend her piece to be a comment on climate change, and that may be why it is such an effective place to reflect on where we end and the world begins.

McKibben was right to remind the art world of the AIDS crisis and of the role visual culture played in combating the institutional negligence of the U.S. government. But climate change is a different kind of crisis, one that requires a different kind of art. This is a catastrophe in which we are all complicit and all at risk. The scale is simply too vast for any didactic artistic critique to feel adequate. As a species with relatively short lives and even shorter attention spans, humans struggle to grasp the long-term scope of an evolving emergency they will not live to experience in full. The most effective protest art, then, does not confront us with evidence we’ve already proven perfectly willing to ignore. Instead, it broadens the narrow ways in which we tend to conceive of time and our position within larger ecologies, without necessarily mentioning climate change by name. The resulting works are not demands for immediate action but ones that expand our psychological capacity to act.

Environmental destruction has been a fact of life since at least the Industrial Revolution. It’s only recently, though, that artists have begun to acknowledge these issues in their work. The Hudson River School painters, for instance, may have privately lamented ecological ruin, but their works depicted rapidly vanishing wilderness as timeless, immutable and impervious to human influence. “I cannot but express my sorrow that the beauty of such landscapes are quickly passing away — the ravages of the ax are daily increasing — the most noble scenes are made desolate, and oftentimes with a wantonness and barbarism scarcely credible in a civilised nation,” wrote Thomas Cole, who helped popularise an idealised and sublime view of the natural world. When Cole painted his early masterpiece “Falls of the Kaaterskill” in 1826, the Hudson Valley site was already a tourist destination complete with a railed viewing platform. Cole, however, eliminated these interventions and added a small, solitary Native American figure to convey a sense of untouched grandeur.

Explicitly environmental art — works that address human-authored threats to local and global ecologies — did not appear until after the 1962 publication of Rachel Carson’s “Silent Spring,” the celebrated exposé of chemical pesticides, which made pollution an urgent national cause. Images of burning rivers, oil spills and animal casualties prompted 20 million Americans — one-tenth of the U.S. population at the time — to stage demonstrations in towns across the country for clean water and air on April 22, 1970. The artist Robert Rauschenberg, who grew up despising the rank smells of the oil refinery in his heavily polluted hometown of Port Arthur, Texas, responded with “Earth Day,” a poster benefiting the American Environmental Foundation, that same year: Black-and-white photographs of pitted landscapes, factories, trash and an endangered gorilla surround a nicotine-brown image of a bald eagle. Nature had ceased to be a pure and timeless muse for artists, instead becoming something vulnerable that humans had abused. In 1974, the photographer Robert Adams published “The New West,” a book depicting human-altered landscapes in Colorado: suburbs, strip malls and land for sale on the outskirts of cities and towns, areas where the natural and the manufactured collide and compromise each other. This period also saw the emergence of land art — vast outdoor projects that interacted with nature — some of which were actively environmentalist in spirit, notably the work of Agnes Denes, whose most iconic works include an entire forest planted in Finland between 1992 and 1996.

More recently, artists have made these fraught borderlands their canvas. Mary Mattingly, who grew up in a Connecticut farming town where the drinking water was polluted, has focused on public works that often involve entire communities. Riled by a century-old ordinance that made it illegal to forage on public land, Mattingly planted a garden on a barge, docking it at sites around New York City, including in the South Bronx. People who lack easy access to grocery stores could come gather as much fresh produce as they wanted. With massive crop failures and famine predicted by climate scientists, the work speaks to the future as much as it does the food access problems dogging the present.

“Limnal Lacrimosa,” Mattingly’s new project, is currently on view in a former brewery in Kalispell, Mont. Melting snow on the roof is channeled inside, where it trickles into lachrymatory vessels — containers that ancient Roman mourners used to catch their tears. The water overflows, spilling onto the floor, before getting pumped back up. The space echoes with drips that keep “some sort of abstract glacial time,” she said: slower when it’s cold, faster when it’s warm. Inspired by the accelerating cycles of melt in nearby Glacier National Park, the piece is an oblique way of engaging with global warming in a state where, Mattingly said, “it doesn’t seem as realistic always to talk about climate change in a way that I might in New York, where it’s pretty accepted.” Still, the work has become a means of establishing common ground. “The political layer comes last,” she said. “Usually, I walk people through it, and then by the end of the conversation, I talk about how fast the cycles of rain and melt are changing. And people completely agree. But if I start with climate change or if I even say ‘climate change’ at all … you can tell people bristle, and they’re not really up for that.”

Mattingly’s is part of a group of works that encourage the kind of behaviour essential to combating climate change — collaboration and cooperation between strangers. What the artists behind these works have in common is their incessant self-examination: How are they contributing to the disaster through their art? In 2019, the painter Gary Hume (whose canvases do not depict especially environmental subject matter) asked his studio manager to research the emissions associated with shipping his works from London, where he is partly based, to New York, where he was having a show at Matthew Marks gallery. Danny Chivers, a climate change researcher, found that sea freight would reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 96 percent compared to air. “There was no downside,” said Hume. Shipping the work by sea was also significantly cheaper. “I was ashamed at myself that it had taken me so long,” he said.

For some, the idea of environmentally conscious contemporary art is a contradiction in terms. The art world is almost comically ill-equipped to address climate change, because the commercial sector runs on unbridled decadence. At Art Basel Miami Beach last November, Dom Pérignon launched a yacht concierge service that, for $30,000, would deliver 33 vintage bottles and caviar to anchored boats in Biscayne Bay and waterfront homes on artificial islands. Dealers court artists with dinners full of fist-size truffles. Collectors reward their advisers with Gucci totes. By masking luxury consumerism in lofty ideals, the art world offers itself up for satire.

In fact, the day-to-day operations of many galleries are built around more banal forms of excess that elide easy parody but are equally pernicious. Art fairs like Frieze and Art Basel, which have editions throughout the year in cities around the world, entail the construction of temporary venues that are destroyed after the parties wrap up, the private jets take off and everybody moves on to the next one. Art fairs “by their nature are inherently unsustainable,” said Heath Lowndes, the managing director of the Gallery Climate Coalition (GCC), an international group attempting to reduce the environmental impact of the industry. “If you think about Frieze, it’s a temporary structure. It’s like building a small town that lasts for five days.”

The GCC offers members a means of calculating their emissions and asks them to pledge reductions of at least 50 percent by 2030. Originally designed for galleries, the organisation now counts museums, auction houses, shipping companies, nonprofits, artists and advisers among its 700 members, some of whom have publicly released the results of their carbon reports. Thomas Dane Gallery, which maintains branches in London and Naples, Italy, reported about 100 tons of CO2 emissions associated with art transport for the year 2018-19. Hauser & Wirth, which has 14 branches and represents dozens of artists and estates around the world, reported producing close to 8,600 tons of CO2 in 2019, more than half of which stemmed from art shipments.

The group is lobbying insurance companies to adjust boilerplate contracts that needlessly stipulate air transport instead of sea freight, as well as creating networks through which galleries can share and reuse exhibition elements (plinths, pedestals) and shipping materials (crates, blankets and other packaging). But the biggest hurdle may be adjusting the expectations of high-profile collectors accustomed to instant gratification. Gallery directors, said Lowndes, have told him they worry that insisting on sea freight or “scruffy” recycled packaging might cost them sales. These are not “technological issues,” said Lowndes. “These are social hurdles.”

An even more glaring contradiction is the fact that art world institutions, the museums we tend to afford a higher ethical status than the commercial sector, rely on funding from the very private enterprises that have contributed so much to the crisis. “These days, it isn’t the Medicis who are using the arts to launder their reputations — it’s corporations and billionaires, including fossil fuel giants and the banks who fund them,” wrote Chivers in a recent piece for The Art Newspaper. Although a number of arts venues “have dropped their oil company branding in the last five years, some, including London’s British Museum, still have promotional deals with the likes of BP, providing a veneer of respectability to the companies most responsible for the climate crisis.”

The museum rebuttal usually goes something like this: Corporate funding comes without strings, and sponsors do not influence programming. And yet nearly every major institution that is tasked with protecting our cultural heritage is underwritten in some way by corporations and people with varying degrees of involvement in the destruction of the planet. In New York, the majority of protests against what activists term toxic philanthropy have focused on perceived human rights violations by individual trustees. Warren Kanders resigned from the board of the Whitney Museum of American Art in 2019 amid outrage over his company’s production of tear gas canisters. That same year, the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum and the Metropolitan Museum of Art barred donations from the Sackler family for its role in creating the opioid crisis. Last year, Leon Black agreed not to seek re-election as chairman of the board of the Museum of Modern Art after protests from artists and activists who cited his close financial ties to the convicted sex offender Jeffrey Epstein.

When will the environmental politics of board members draw the same ire from activists? There is little sustained outrage over the fact that in order to enter the Met, you first have to commune with a Las Vegas-style fountain by the front entrance that bears the name of David Koch, who denied the existence of climate change up until his death in 2019 and, in the words of Greenpeace, “actively financed efforts to rally the public against the scientific community.” Last spring, protesters staged several demonstrations directed at Patricia Phelps de Cisneros, a MoMA trustee whose husband, Gustavo Cisneros, sits on the advisory board of the Barrick Gold Corporation, which mines gold and copper in 13 countries. “When you look at the Barrick Gold company and we think about the presence of people like the Cisneros family, you’re looking very blatantly at ecocide,” said Michael Rakowitz, a sculptor and installation artist who has been a prominent figure in related protests. “You’re looking at the poisoning of entire communities and spots of land and rivers in Central and South America.”

But trustees at other New York museums with ties to mining operations and the fossil fuel industry have so far avoided controversy. Daniel Och, whose hedge fund paid $413 million in penalties over a foreign corruption scheme that involved bribing officials in Libya, Chad, Niger, Guinea and the Democratic Republic of Congo to secure exploratory mining and energy concessions, sits on the MoMA board alongside de Cisneros. Susan K. Hess, whose husband is the chief executive of the oil and gas supplier Hess Corporation, is a trustee at the Whitney. When environmental art exhibitions occur at institutions with funding that undercuts their professed ideals, those exhibitions become a smoke screen for the ethical dissonance of the art world. “One of the things that critical and political art does is reinforce the narcissism of the field and our self-representations in fighting the good fight and being on the right side of history,” said the artist Andrea Fraser, whose work often critiques the art world’s machinations. “I don’t think we’re part of the solution. I think we’re part of the problem.”

If our current relationship to time produces inertia, some of the most powerful works today ask us what we want the future to look like, at a moment when the very prospect of a future is in question.

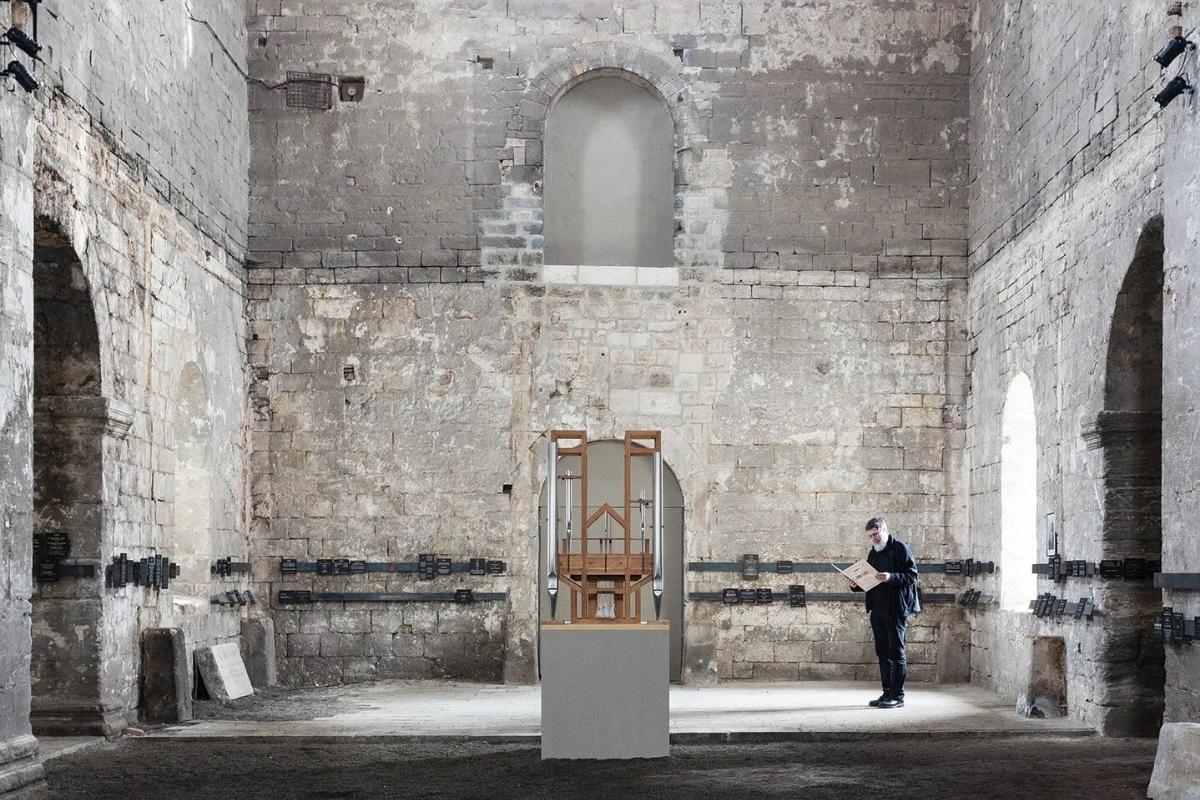

With this in mind, I travelled to a church in the remote town of Halberstadt, Germany, in February to see the world’s slowest musical performance, which, 21 years on, is still in its infancy. An experimental composition by John Cage called “Organ²/ASLSP,” the piece began in 2001 and will end in 2640. Originally written for piano in 1985, the score carries the provocative tempo instruction “As slow as possible.” Sandbags suspended from the pedals of a small wooden organ in the transept maintain a deep, droning seven-note chord, which has been reverberating continuously since 2020. Chord changes are rare — they usually happen every few years — and in February, a crowd had gathered to witness one. They waited for the new sound, radiating the same jittery, communal reverence that precedes a total eclipse: The chill air inside the medieval church hummed with suspense.

Cage reworked the piece for organ in 1987 and, in 1998, a few years after his death, a group of composers, organists, philosophers and musicologists began discussing the limits of slowness, considering the life expectancy of wooden organs. The piece will depend on generations of human cooperation and care to survive. Both the organ and the St. Burchardi Church, which is older than Magna Carta, will need maintenance to endure. The project forces listeners to think beyond their own life spans, to participate in something that not even their great-great-great-great-grandchildren will live to see finished. The organ represents a relationship with unborn strangers; each chord asks us to ensure that there is a future in which the next one can sound.

Six hundred and eighteen years from now, when the performance is slated to end, the town of Halberstadt may be flooded, said Rainer O. Neugebauer, a retired social sciences professor who leads the foundation responsible for the piece. It may be a desert. Tornadoes may have tugged the medieval building off the ground. In the last 20 years, unusually strong winds have ripped away parts of the roof, sending tiles crashing into the space around the organ. Still, he chooses to believe that it will endure. Great art, he said, connects us to what might yet be possible.

It was time for the chord change. Ute Schalz-Laurenze, the white-haired former director of a local music program and competition, gently removed the pipe playing G sharp and the drone of the organ softened into a new sound that will echo through the battered church for the next two years. The crowd listened and, as the note changed, they cheered.

Neugebauer does not know whether the organ project in Halberstadt can physically or financially survive. But for him, that uncertainty is part of the piece. Gesturing to the organ, he said, “This is my idea of hope.”