Benjamin Comar knows a lot about very nice things. The Piaget CEO has been working in the luxury industry for three decades with previous roles including head of marketing for Cartier, fine jewellery director at Chanel and chief executive at the rather more avant-garde jewellery house, Repossi. In the following interview, Comar shares with T Australia what he’s learned along the way.

You’ve worked in the luxury industry for 30 years. Growing up was it always a world you wanted to get into?

Growing up, I think, I wanted to be a lawyer. I didn’t expect to fall into luxury at all. But I did an internship at Richemont for Cartier. And once you get into the jewellery and watch business, it’s very hard to get out of. For me, it was almost like an addiction. That’s because we’re selling joy. We’re selling happiness. We’re selling special moments to the customer. It’s not like we’re selling insurance. I mean, I have nothing against selling insurance – it’s necessary – but it’s also less sparkly than jewellery and watches.

Given your experience in the industry and your roles at Cartier, Chanel et al, if you could go back and give your 20-year-old self a bit of advice about working in the luxury sector what would you say?

I worked in Japan for a few years with Cartier. When I was there, I heard a sentence that stayed with me that was: “I can’t, but we can.” Understanding that ethos is probably the most important thing about working in luxury. Because success in this industry depends on that combination of the manufacturing and the craftmanship, coupled with the expertise of the marketing and sales teams. Success in luxury is an interplay between all those elements. Without a team spirit here, you have nothing.

It’s interesting that idea got drilled into you in Japan where, traditionally, that sense of the collective is so strong. There’s that Japanese proverb that says: “The nail that sticks out gets hammered down”.

Yes, in Japan, the community is more important than the individual. The success of the company is more important that the individual. And that’s something that I’ve become aware of with Piaget. This brand was founded in 1874, it was there before me and it will be there for long after me. My job with the team is to continue building the brand’s equity for the future generations. Nothing else.

Looking at it like that, it sounds like you’ve always recognised that you’re the brand custodian of Piaget for this limited window of time. What did you want to do with that opportunity when you took on the role? What was your vision?

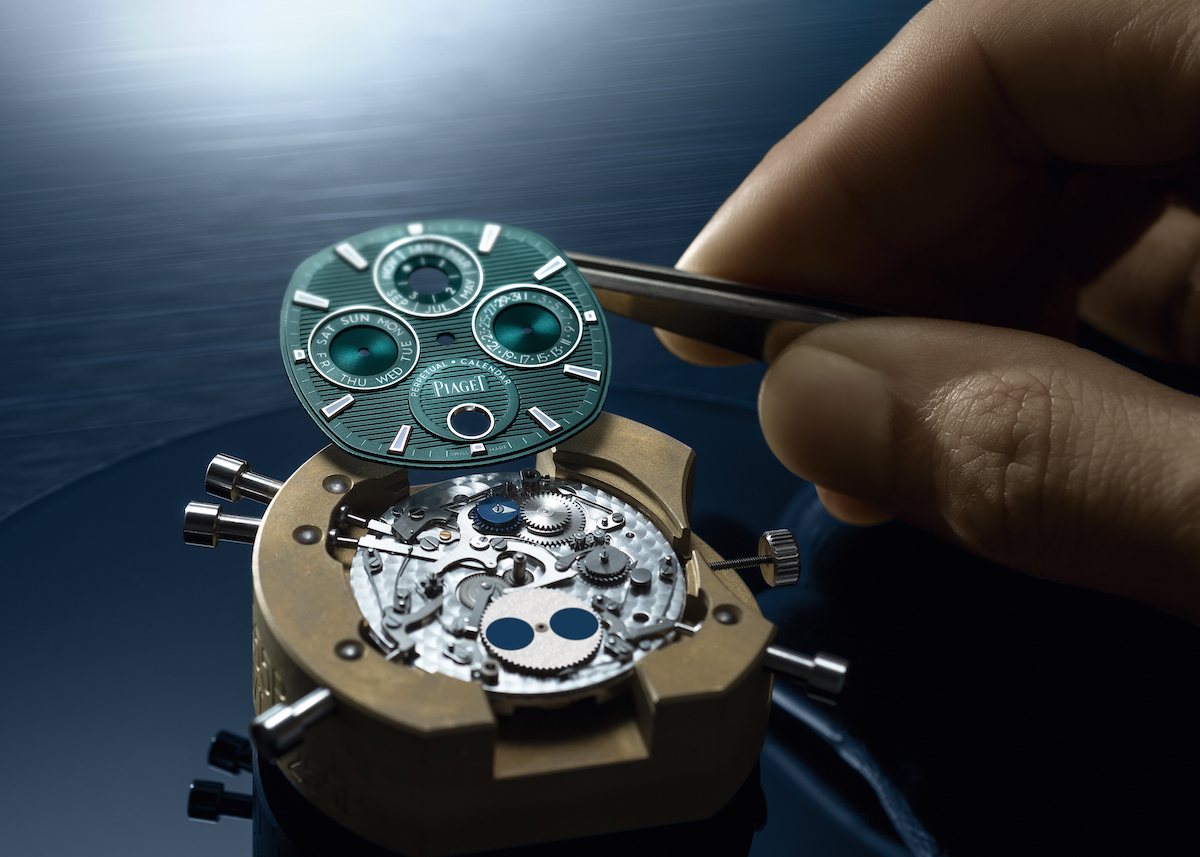

What I really wanted to do was the define the DNA of this brand and tap into what it’s really about. I love the dichotomy of Piaget. It was born in the Swiss Jura in 1874. making movements for third party watchmakers in Geneva. That’s where that culture of craftmanship and excellence was founded. But then after the war, Piaget started to make their own products. Not only did they start making jewellery and watches, but they were making a lot of really crazy and very fancy stuff. That was interesting because Geneva, at the time, was very classical and very traditional. But these more glamorous products really appealed to customers in places like Monaco, Monte Carlo and the US that were more relaxed and wanted more extravagant and more joyful products. I remember saying to the person at the Piaget who was responsible for that direction, “Where did these more exuberant products come from?’. And he said: ‘I didn’t want to be like the others. I wanted to do something different.

I was interested in the dichotomy of these two pillars – one that was all about craftsmanship and elegance, while the other was all about ‘70s extravagance. There was this tension between the two elements that I wanted to show.

I remember getting a sense of jet-set glamour hearing about the launch of the Piaget Polo in 1979…

Yes, that watch was launched in Palm Beach in Florida at the World Polo Cup with Ursula Andress. For me, that idea of ‘70s glamour in a very chic way is what Piaget really is about, albeit a modernised form of that today.

The other thing about Piaget, of course, is that it’s a brand with an emphasis on both watches and jewellery. There’s not many brands with that dual focus – I can think of Cartier, Bulgari, Chopard and that’s about it. As a CEO how do you juggle those two core focuses? Is it inevitable that one will always overshadow the other?

I try to keep an equal footing between them and maintain that sense of balance. They’ve very much the two legs of the brand. We don’t want to focus too much on watches and we don’t want to focus too much on jewellery. For me, it’s a question of always trying to balance the two.

How has the luxury market changed in the last 30 years?

So much has changed in terms of both globalisation but also democratisation. Thirty years ago, luxury was more an illustration of power and was often reserved for more formal occasions like weddings. Now I think it’s become more relaxed and is now more about hedonism and indulgence. The growing independence of women also means that luxury items are no longer mainly bought mainly as gifts – women freely buy them for themselves and not necessarily just for special occasions either. Today, I think that luxury is more about pleasure and indulgence.

During all this time that you’ve worked in this high-end industry, what have you changed about the way you approach your work?

For me, I think it’s pretty basic. As you get older, you listen more to other people! When you’re young you’re naturally keen to express yourself a lot and be heard. But experience has taught me to try to listen more and really understand what other people are bringing to their table. In particular, I find, the energy of the young generation is very important. The more I’ve been in a position as a manager, the more I’ve realised the value of listening to others.