How do we define furniture? It might seem like a silly question, but it’s one that kept coming up in October of last year, when, in a conference room on the 15th floor of The New York Times building, six experts — the architects and interior designers Rafael de Cárdenas and Daniel Romualdez; the Museum of Modern Art’s senior curator of architecture and design, Paola Antonelli; the actress and avid furniture collector Julianne Moore; the artist and sculptor Katie Stout; and T’s design and interiors director, Tom Delavan — gathered for nearly three hours to make a list of the most influential chairs, sofas and tables, as well as some less obvious household objects, from the past century.

The goal was to land on a wide range of offerings, but there were parameters: To qualify, each piece was required to have been fabricated, even if just as a prototype, within the past 100 years. It also needed to be at least slightly functional. (The Japanese architect Oki Sato’s 2007 Cabbage chair, a treatise on sustainability constructed entirely from a roll of disused paper, isn’t the sturdiest place to sit; nonetheless, it was nominated.) Lighting was excluded from the debate — “which is nuts,” said de Cárdenas, a former men’s wear designer who started his firm in 2006 — unless it was attached to, say, a desk. (The Italian architect and designer Ettore Sottsass’s illuminated Ultrafragola mirror, which presaged selfie culture by decades, made the cut.) There were no limits placed on provenance, and a piece didn’t need to have been designed by a known name, or even attributable. The jurors were determined to avoid what Antonelli described as “the usual collectors’ items by white German, French and Italian males with a smattering of women, no Latin American or Black — and very little Asian — representation.” While the final list, presented below in roughly the order it was discussed, and not reflecting any kind of hierarchy, does include an icon or two (to omit Charles and Ray Eames or Le Corbusier, the group decided, would be a mistake), diversity of maker (and of materials, styles, processes and prices) was a consideration. In each case, the objects represented more than comfort or utility; every innovation is, in its own way, a historical artifact — a response to the prosperity or unrest into which it was born or a proposal for a more efficient world, maybe a better one.

The participants were asked to submit a list of 10 suggestions beforehand, revealing their own unique tastes and interests. Stout, who curated a show in 2020 with the Shaker Museum in Chatham, N.Y., argued that a bonnet is a slipcover for the head and should count as furniture. (She was voted down.) Moore, an avowed minimalist, petitioned to include austere creations in marble or wood by Poul Kjaerholm and Donald Judd. Romualdez’s more classical choices — among them a daybed by the mid-20th-century French designer Marc du Plantier and a patinated bronze table by the Swiss sculptor Diego Giacometti from the 1980s — were influenced by the luxurious interiors he saw in American magazines while growing up in Manila in the Philippines, long before he’d work for the architects Thierry Despont and Robert A.M. Stern and later open a firm of his own. As Delavan said, “Daniel’s were the chicest. Julianne’s were the purest. Katie’s were the wackiest. Rafael’s were the campiest. And mine were the dullest.” Antonelli’s were, perhaps, the most comprehensive: She created three separate lists to accommodate her top picks, runners-up and wild cards. “I just want us to express an idea of design that excites the world,” she said. As the members of the group settled into the room’s upholstered cantilever chairs — imitations of a Bauhaus style popularised in the 1920s by the Hungarian German Modernist Marcel Breuer — they nodded and offered words of encouragement. And then they got down to business. — Nick Haramis

1. Piero Gatti, Cesare Paolini and Franco Teodoro, Sacco Chair, 1968

Considered the original beanbag, the Sacco chair is the rare design object to become an instant classic in both rec rooms and museum collections. It was included in MoMA’s seminal 1972 show “Italy: The New Domestic Landscape,” which presented furnishings that looked beyond aesthetics and function and toward sociocultural shifts, including the rejection of bourgeois propriety. “Imagine trying to be stuffy while slouching in a beanbag chair,” said the show’s curator, the architect and industrial designer Emilio Ambasz. Indeed, the vaguely pear-shaped blob of stitched vinyl filled with polystyrene beads — the transparent prototype was partially inspired by piles of snow — moulded to the body of the sitter and encouraged lounging of the highest order; the hard part was getting out of it. Now that we better understand the environmental impact of polystyrene, the Italian furniture company Zanotta, which has produced the piece from the start and continues to call it the “anatomical easy-chair,” has experimented with a version stuffed with bioplastic derived from sugar cane. — Kate Guadagnino

Tom Delavan: It was revolutionary in terms of material, and it really did filter down to so many imitations that are less expensive. It also addressed how people’s lives were changing: We’re slouching lower and lower as time goes by.

Paola Antonelli: I used to say it was like the Kama Sutra: It has tons of positions. And it was a symbol of an era. I remember pictures of bearded revolutionaries smoking their joints on it. It was all about huddling together and rethinking the world, and it’s still as fresh as ever. I love the fact that you can find it in different shapes. My only big concern about that chair is sustainability. But there’re so many other fillers beside polystyrene, right? I think you can use mushroom mycelium.

Katie Stout: I wish we were all lounging on beanbags right now.

2. Le Corbusier, LC14 Tabouret Cabanon, 1952

Some of the best design originates at home. A great example is the LC14 Tabouret Cabanon, which the Swiss-born French architect Charles-Édouard Jeanneret, known as Le Corbusier, built for his cabin in Roquebrune-Cap-Martin, a vacation shack that he designed (reportedly in 45 minutes) on the French Riviera. At roughly 160 square feet, the residence was almost monastic, with most of the furniture built in. An exercise in pure functionality, the boxes can be used as chairs, side tables and storage. Made of wood — the Cabanon is chestnut, though other iterations come in oak — they were inspired by a whiskey crate the architect found on the beach, with dovetail joints and oblong holes in the sides for lifting. Prefiguring both modular furniture and the nothing-to-hide sensibility of industrial décor, they serve as rustic altars to the right angle, about which Le Corbusier once wrote, “Simple and naked / yet knowable. … It is the answer and the guide.” — Rose Courteau

Julianne Moore: In my business, this is what we call an apple box. I stand on one if I’m shorter than the actor I’m working with. Le Corbusier created an object of desirability, but it’s something you could make yourself and use a million different ways. [The English furniture designer] Jasper Morrison did his own version. I have two in my house that were built by a grip to hold a certain kind of camera. A painter once said to me, “They’re sort of amazing. They look like a [Constantin] Brâncuși [sculpture].” It’s a simple object that reminds different people of different things. And while it’s sort of silly that the Corbusier version has become this untouchable museum piece, I like the fact that it’s just a box.

Delavan: I’m going to argue against it. You can’t say that Le Corbusier invented the box. My feeling is that he was basically reusing a thing that already existed.

Rafael de Cárdenas: I’m not defending it, but he did recontextualize it.

Antonelli: Even though I’ve never been a fan of this, I buy your argument. I had [the Italian architect and designer Achille] Castiglioni as a teacher. And he used to always say that redesign is a legitimate form of design — to take something that exists in the world and appropriate it and improve upon it.

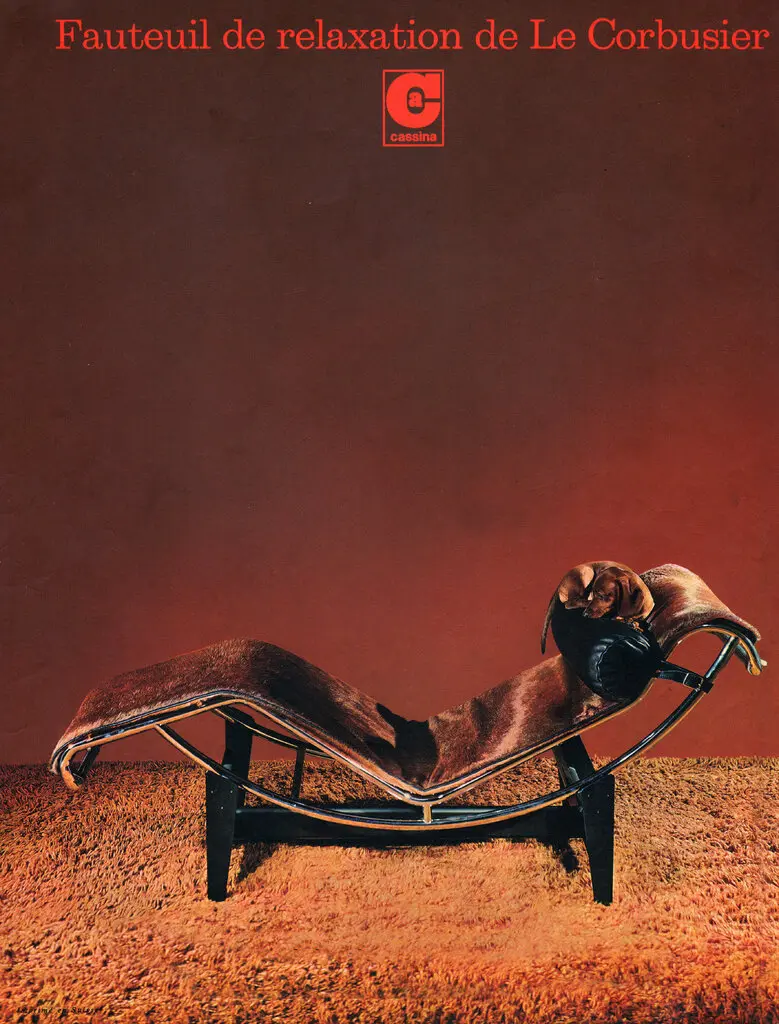

3. Le Corbusier, Pierre Jeanneret and Charlotte Perriand; Chaise Longue à Réglage Continu; 1928

In 1929, Le Corbusier, along with his cousin Pierre Jeanneret and their colleague and fellow architect and designer Charlotte Perriand, created a Modernist interior for the Salon d’Automne art exhibition in Paris. In a sly rejection of the enameled embellishments of Art Deco, the prevailing style of the time, they presented concealed lights, glass-topped tables, mirrored cabinets and seating featuring tubular steel, including the lissome Chaise Longue à Réglage Continu, which they’d first produced and placed the previous year in a villa just outside of Paris. With an H-shaped, bicolor-steel base cradling chromed tubes that followed the form of a supine human body — dipping to accommodate the hips and cresting to support the knees — it was among the first ergonomically conscious pieces of furniture ever manufactured. The frame, which could be adjusted to change the angle of repose, held a slim, black fur mattress with a cylindrical headrest. Far too radical for its time and expensive to fabricate, the piece languished for decades but emerged as a coveted emblem of Modernism when Cassina started producing it in 1965. Le Corbusier, who held functionality in high esteem, is famous for saying that a house is a machine for living. It’s no surprise, then, that he considered this chaise longue a machine for resting. His biographer Charles Jencks had another take: “It is as if the body is being propped up on fingertips like a precious jewel.” — K.G.

Delavan: I love this chair because, even though it looks weird, it addresses how our bodies are meant to sit. It’s ergonomic in a way that chairs or sofas weren’t before. Every zero-gravity chair is a version of this.

Antonelli: Interestingly, for a piece of modern furniture, it’s also comfortable.

Moore: And it references what was going on in the world at the time: industrialism and metal suddenly entering our lives and our homes.

Delavan: Think of how crazy this must have seemed in 1928.

Moore: When so many people were still living with traditional furniture.

Antonelli: If we’re to include a tubular steel chair, this is the one.

4. George Nakashima, Slab I Coffee Table, Circa 1950

These days, live-edge furniture — fashioned from a slice of a log with at least one side left ruggedly intact — seems to be everywhere. Each piece owes a debt to the raw splendour of George Nakashima’s original slab coffee tables. Nakashima, who was born in Spokane, Wash., to Japanese immigrant parents, established himself as a furniture designer before being imprisoned with his family at the Minidoka internment camp in Idaho during World War II. While there, he further refined his woodworking skills under the tutelage of a fellow internee, the master carpenter Gentaro Kenneth Hikogawa. After Nakashima’s release in 1943, he settled in New Hope, Pa., where he established his own studio and made furniture for Knoll. Believing that his work gave trees a second life, he fused the austere solidity of Shaker furniture with the Japanese concepts of wabi, sabi and shibui — emphasizing age and simplicity. This bundle of ideals was best expressed in the Slab table, with a top made from a single slice of American black walnut or cherry, occasionally accented with functional elements like a stabilising butterfly joint. Instead of excising the irregularities and imperfections, Nakashima chose to highlight them, a radical approach at the time. Each table was unique to the tree and the woodworker who handled it. The furniture designer enshrined sensitivity, not domination, as the key to sublime design, in contrast to the ornate embellishments of Art Deco and the factory aesthetics of the postwar era, which embraced machinery as a human triumph. — R.C.

Moore: I’m obsessed with craft, and I think that Nakashima was the first person who brought it into mainstream conversation. I think about what he went through, how he emerged from the internment camp and returned to making his furniture. You could go to New Hope and say, “I want a table, some chairs and a bed,” and he would do it. He was expressing himself as an artist and introducing this idea of organic Modernism.

Delavan: This table inspired a lot of craftspeople to be like, “I can make one, too.”

De Cárdenas: There’re also kitsch versions of it. So much defining furniture is high culture, but this had mass appeal.

Antonelli: I like that it inspired people to make their own little monsters.

5. Bill Stumpf, Ergon Chair, 1976

The ancient Greeks made chairs with curved backrests, but it wasn’t until the 1970s that ergonomics, the study of people in their workplace undertaken to improve efficiency and welfare, was heartily embraced by industrial designers. That’s when Herman Miller brought on the American designer Bill Stumpf, who’d worked with medical experts while doing postgraduate research at the University of Wisconsin to conduct studies on ideal sitting posture that incorporated X-rays and time-lapse photography. In 1976, the year that word processing became available on microcomputers, Stumpf came up with the swiveling Ergon office chair, constructed with pillowy pieces of fabric-covered foam (one for the back and another for the bottom), which could be wheeled in any direction. The chair also had gas-lift levers that controlled height and tilt — good news for women, who were joining the work force in record numbers, and whose comfort had been ignored by earlier designers. But Stumpf didn’t stop there; in collaboration with the Los Angeles-born Don Chadwick, he went on to debut 1994’s Aeron chair, which featured a higher backrest covered in a flexible textile called pellicle. It remains, with a tweak or two, one of those pieces that’s so ubiquitous you’re not likely to notice or think about it. That is, until a co-worker nabs yours. — K.G.

Delavan: It’s one of the earliest examples of an adjustable office chair. Part of it was that women were now in the workplace, so they needed the chair to be a different size. Paola, you’d nominated the Aeron chair, which is great, but I feel like Stumpf’s idea started here. The Aeron is a refinement of the Ergon.

Antonelli: I saw the Aeron chair being made when I was living in Los Angeles, and I remember it in the World Trade Center lobbies. It’s the first thing I acquired for the Museum of Modern Art when I started working there. But I prefer this one because it’s earlier. There was the Ettore Sottsass chair for Olivetti — the yellow one [from 1972] — but I don’t care, because this one was probably more affordable, and it went everywhere.

6. Gae Aulenti, Table With Wheels, 1980

The “High Tech” moment in design started in the early 1970s, as more and more New York City artists were moving into lofts in SoHo’s abandoned cast-iron buildings and furnishing them with functional pieces picked up at hospitals, offices, warehouses and restaurant supply stores. In these open-plan homes and those that aspired to be like them, you were likely to find white walls, exposed pipes, track lighting, Metro Super Erecta wire shelving and stainless-steel commercial refrigerators. In 1980, at the tail-end of that era, the Italian architect and designer Gae Aulenti introduced Table With Wheels, a thick pane of beveled glass mounted on large rubber casters that she intended to resemble the wooden trolleys used to cart heavy pieces around the factory of Milan’s FontanaArte design studio, where she served as art director. The table had the playfulness and poeticism of a Marcel Duchamp readymade, and it presaged glass as one of the decade’s trendy materials for interiors — one seen increasingly throughout the 1980s in the form of smooth reflective surfaces and chunky, semitransparent blocks. In 1993, Aulenti riffed on her design, releasing Tour, an updated model with bicycle wheels. — K.G.

De Cárdenas: I know it’s just a piece of glass on casters, but I think it transcends class, style and era.

Moore: You know what else it speaks to? High-tech design.

Daniel Romualdez: If we’re doing high tech, I think we should include the Metro shelves.

Moore: No! That then knocks out Dieter Rams.

7. Dieter Rams, 606 Universal Shelving System, 1960

The German functionalist Dieter Rams didn’t invent modular design, but as the creator of the 606 Universal Shelving System for Vitsoe, he can be credited as one of its early perfecters. The system’s construction is strikingly simple, with aluminium E-Tracks mounted to walls from which shelves, cabinets and even tables can be hung using no-equipment-required pins. Adjustable and customisable, it can be adapted to a wide range of spaces, needs and aesthetics. (When they’re full, the wafer-thin but deceptively strong shelves, made of powder-coated, laser-cut steel, nearly disappear.) The unit embodies all 10 of the design principles that Rams, an early advocate of environmental sustainability, formulated in the 1970s (No. 1: “Good design is innovative”; No. 5: “Good design is unobtrusive”), but the real reason it’s been revered for decades may be its incomparable durability (No. 7: “Good design is long-lasting”). Parts purchased today can be used interchangeably with those from 1960, when the shelving first went into production. — R.C.

Moore: I’m going to go to bat for Dieter Rams. I’m a big fan of the idea of a system, particularly in terms of the 20th century and how we started to live [in a more transient way], which led to things that collapse or stack and are lightweight. The idea is that you can buy this piece and change it — use it for books, records or clothing. I’m really interested in industrial design, a lot of which we don’t even think of as being designed. It often seems to have come out of nowhere, and I feel that way about this shelving.

Antonelli: If we’re going to include a shelving system, much as I love Metro’s [steel storage] shelves, Dieter Rams should be on here.

Moore: He’s a rock star.

Stout: Even just this image [from the Vitsoe catalog], with a game of Twister stored on a shelf, feels so democratic to me. All these different tiers of design.

Moore: I love the Vitsoe catalog, frankly. It’s very soothing.

8. Faye Toogood, Roly-Poly Chair, 2014

Faye Toogood’s Roly-Poly chair, which debuted in 2014 as part of a collection of similarly rotund fibreglass furniture titled Assemblage 4, isn’t just a seminal piece of design — it’s also got a sense of humour. The key lies in the contrast between its jolly, potbellied seat, evocative of a cartoon animal, with four squat, cylindrical legs, and the confident way it occupies space. The chair is a corporeal symbol of maternal strength; Toogood, a multi-hyphenate British clothing and interior designer, has said that the roundness was inspired by her pregnancy. (“I’ve got fat,” she told an architecture magazine upon the chair’s release.) Indeed, it’s the kind of perch that makes you never want to get up, to relinquish your vanity and drop into a state of permanent comfort. With no hard edges, it’s both cleverly child-safe and endlessly imaginative, conjuring bubble letters, elephants and balloons. But although the Roly-Poly grew out of the designer’s experience with her changing body, it offers something more universal: a softer, more whimsical take on minimalism, which in recent years has turned away from sharp-cornered austerity toward the more organic silhouettes of the circle and the arch. — R.C.

Moore: Faye was at the forefront of a movement where things suddenly got soft.

Antonelli: And big.

Delavan: She changed the silhouette.

De Cárdenas: I remember her presentation in Milan in 2011. There were these black hard-boiled eggs, and cheese served on pieces of charcoal. I mean, it sucked scraping your teeth on stuff, but it was also cool. And then there was furniture, but the whole thing was the presentation. Whatever that is, some people do it well and most people don’t. But I think she started it. Everything in design at the time was slick and boxy, highlighting craftsmanship, but this work wasn’t.

Delavan: It felt like something she could have sculpted.

Moore: And it was new. It’s always exciting to be woken up like that.

9. Unknown, but Possibly Jean-Michel Frank; Parsons Table; Circa 1930

Some pieces of furniture are so unobtrusive and chameleon-like that they hardly feel designed. Such is the case with the Parsons table, whose defining feature is its ratio: No matter the table’s size, its legs — which stand flush with the corners of its surface — must always be equal in width to the thickness of its top. It’s thought to have emerged from a design project completed in the early 1930s at the Paris satellite of New York’s Parsons School of Design, the result of an assignment often attributed to the aristocratic French decorator Jean-Michel Frank, who was a lecturer there at the time. (The American designer Joseph B. Platt is also often cited as having a hand in the piece.) Known for creating magisterial spaces for the fashion designer Elsa Schiaparelli and the composer Cole Porter, Frank put aside his usual interest in such sumptuous materials as shagreen and obsidian, challenging the students to design a table so elemental that it would retain its basic character and integrity regardless of finish. — R.C.

Romualdez: Leading up to this debate, I asked ChatGPT for a list of influential furniture and nothing surprised me. [But] I wanted to [choose items] that influenced me personally. Growing up in the Philippines, I only saw things in magazines — like [1960s François-Xavier] Lalanne sheep [sculptures]. They were in Valentino [Garavani]’s chalet, [Yves] Saint Laurent’s library, the Agnellis’ Milanese apartment.

Moore: Unfortunately, Lalanne sheep are just signifiers of enormous wealth.

Romualdez: Yes, but for me, nose pressed to the glass, it made me question, “What makes something fancy?” People had flocks of them. When Julianne [and I were talking about our lists], she asked, “What’s your favorite dining table?” Although simple and plain, this is the first thing that came to mind.

De Cárdenas: We can’t not include the Parsons table.

Romualdez: A friend of mine, [the American philanthropist] Deeda Blair, used to tell me, “You can’t get an 18th-century coffee table. It’s a conceit of the modern world.” I was attracted to this as a foil to [what’s in] most people’s fancy living rooms.

10. Ettore Sottsass, Ultrafragola Illuminated Mirror, 1970

Although the Italian architect and designer Ettore Sottsass’s undulating electrified mirror, which emits a dusky pink glow, predates social media by four decades, it somehow anticipated the age of the selfie. Sottsass, who would in the 1980s spearhead the madcap Milan-based collective known as the Memphis Group, crafted it as an apparent tribute to womanhood — its ripples supposedly reference flowing hair and body curves. Such an idea may now seem a study in objectification; nonetheless, the mirror’s enchantments are undeniable, as proven by its vibrant second life on social media. The musician Frank Ocean and the model Bella Hadid are among those who’ve captured themselves, like modern-day Narcissuses, in its reflection. The appeal is obvious: It’s seductive, flirtatious and lighthearted — décor as an antidepressant in troubling times. Perhaps Sottsass himself best explained why the glowing, flowing mirror is universally beloved. “When I was young, all we ever heard about was functionalism, functionalism, functionalism,” he once said. “It’s not enough. Design should also be sensual and exciting.” — Max Berlinger

Stout: Sottsass isn’t my favourite, but this has been so influential, especially in terms of marketing and the rise of Corporate Memphis. Even though it’s from the 1970s, it seems to have been made for the Instagram era. He and [the Italian architect and designer] Gaetano Pesce have been so significant to an entire generation of designers, especially right now.

Antonelli: I don’t think we need to include Pesce.

De Cárdenas: Pesce was always niche and was left out of the design conversation for a long time. Now his work feels very relevant again.