When the frontman of the electronic duo Electric Fields says his first performance, at the age of eight, was a rendition of Elvis Presley’s “Blue Suede Shoes” at a school assembly, it hardly comes as a surprise. His class-mates may have held cue cards to help him with the lyrics, but it seems the nascent singer already possessed a preternatural musicality that eluded any genre or style. Like Presley, who was influenced by gospel, borrowed from rhythm-and-blues and ushered in a new, hybridised genre, “rockabilly”, Zaachariaha Fielding would go on to remix and layer music all his own. He just didn’t know it yet.

“I always knew I was going to be an entertainer from a very young age,” says Fielding, 29, who grew up in Mimili, in the Anangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara Lands in South Australia. “I had a good set of pipes, I knew I had a lot of humour and that it was a good combination — it was just a matter of time when it was going to find a home.”

The eldest of nine siblings, he matured quickly and recalls a youth fraught with challenges but filled with joy. Even as a child, he was sensitive to the dualities of life — that it could be both happy and sad — finessing an emotional register that has become the hallmark of his music making. At 14, he moved to Adelaide and eventually auditioned for the shows “The Voice” and “The X Factor” before partnering with Michael Ross to form Electric Fields.

Together, they have won national awards and competed for Eurovision 2019 with their song “2000 and Whatever”. Each track is a mashup of electric soul and Indigenous storytelling, animated by Fielding’s rich, androgynous tone singing lyrics alternately in Pitjantjatjara, Yankunytjatjara and English. The two are 10 years and one day apart in age; Fielding believes their collaboration was kismet. “Michael is a brilliant human being, a musical genius,” he says. “He makes me feel comfortable and loved.”

Still, transitioning from the APY Lands, “where everything is still and not dominated by the clock or rules”, to Adelaide hasn’t been easy. “Western culture has a lot of rules and it just made it difficult to adjust,” he continues. “I’m still finding it hard, but I’m doing OK.”

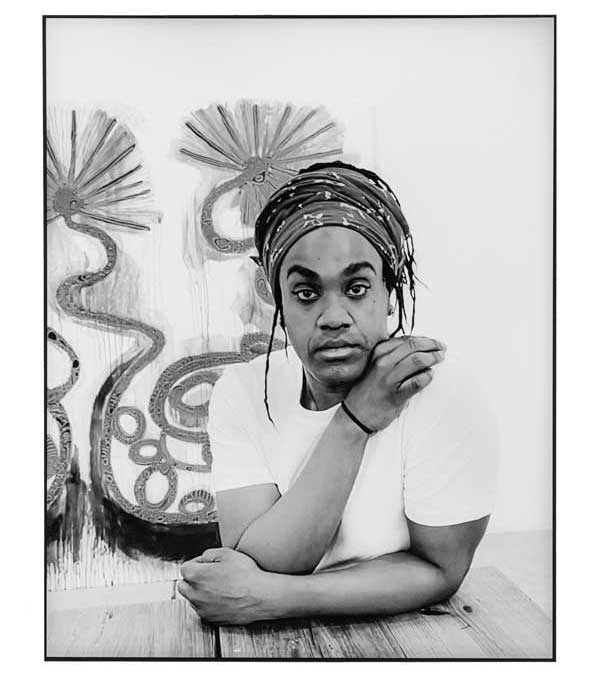

A multidisciplinary artist, Fielding also lays bare the constellations of his emotions, memories and experiences in his artworks. His father is the contemporary artist Robert Fielding, and the younger Fielding has segued into visual arts, which he finds cathartic. His painting “Untitled” is part of the National Gallery of Victoria’s “Queer” exhibition (opening March 18, 2022).

“I cry a lot in my canvases every now and then, and I get angry in my canvases,” Fielding says. “All of my emotions are inside of anything I touch.” Which medium is more therapeutic? “I get the same satisfaction,” he says. “When I’m in the studio, I’m using a different type of brush, it’s my vocals and my tone.” On canvas, “it’s more of a physical thing, but I still leave the work the same as I do offstage”.

Speaking of being offstage — a consequence of recent lockdowns — it’s clear Fielding has missed his audience, whom he calls his “co-workers” and has a great fondness for. The crowd plays a critical and energising role in activating each song.

For now, though, there is a new single and the promise of a return to live performances. “I have a good feeling that it might be on its way back,” he says. “I think there’ll be a new energy at live shows —not in a way that I used to see and feel it, but I’m OK with that. As long as I see a face, I’m all good.”

A NOTE ON THE PHOTOGRAPHY: At the time T Australia commissioned this portfolio, much of the country was in lockdown. As such, our portrait photographer, Kelly Geddes, undertook T Australia’s very first remote shoot, via Facetime and Zoom. Geddes revelled in the challenge, using screenshots and photos of her computer screen to capture the scenes, the latter technique producing some of her favourite pictures. “They had a natural and raw quality to them,” she says. The files were sent to the darkroom service Blanco Negro, where they were hand-printed from a digital enlarger, toned in the darkroom as silver gelatin prints and then scanned for publication as black-and-white images. Each subject wears a T-shirt by the Australian label Nobody Denim; the same style appears in flat lay photographs throughout the portfolio. In these, the T-shirt serves as a “blank canvas”, altered by the subjects in a way that represents the legacy they hope to leave.