There’s no better way to celebrate Saint Valentine’s Day than sampling some of the finest dishes in the Australian dining scene. T Australia editors have put together a curated list of the best dining experiences on offer this year, specifically tailored to create an unforgettable Valentine’s Day set to leave your loved one’s heart (and stomach) full.

La fête de Saint-Valentin at Loulou Bistro, Milsons Point

Inspired by Parisian classics and all-around contemporary European food favourites, Loulou Bistro knows how to dial up the romance this Valentine’s Day. Dine in and enjoy the best of head chef, Ned Parker’s carefully curated three-course Valentine’s menu, available exclusively on February 14. Beginning the evening with a glass of Moët & Chandon Champagne on arrival for each guest, you can expect a feast fit for royalty featuring steak tartare classique, confit duck leg, John Dory, pommes frites and more. Finish with a watermelon and rose granita or mousse au chocolat with preserved cherry and sablé, inspired by the essence of Valentine’s Day itself. Available from 5pm on Friday,February 14 from$125 per person.

Valentine’s Golden Hour at Hacienda, Sydney

Situated in the heart of Circular Quay, sit back and take in the sunset harbour views during Golden Hour at Hacienda. With specialty cocktails including Valentine Clover Club and Valentine Chocolate Old Fashion, the menu features lobster and sesame toastadas served with caviar and Hacienda’s signature late-night fries. Available from 3pm to 6pm on Friday, February 14.

Barentain Dē at Genzon, North Sydney

North Sydney’s Genzo has expertly distilled the art of cooking with modern Japanese essence to create a truly spectacular dining experience. Their full à la carte menu will be available all night – from kushi-stikku (grilled skewers) to premium wagyu beef, fresh sashimi and ohashi (handmade noodles) – paired with selections from their sake room and full beverage list. Available from 5pm on Friday, February 14.

Love is on Fire at Poetica, North Sydney

At first glance, the North Sydney restaurant and bar Poetica appears tailor made for a relaxed and lavish evening on the day of love. The custom three-course set menu including a glass of Veuve Clicquot on arrival, alongside yellowfin tuna with embered tomato and verjus vinaigrette, Skull Island prawn with fermented chilli vinaigrette, dry-aged rib eye, and vanilla custard tart for dessert.Available from 5pm on Friday, from $145 per person.

Sky High Valentine’s at Aster Rooftop Bar, Sydney

Whether a pre-dinner aperitif or end-of-evening nightcap, celebrate Valentine’s Dayyear with a luxury moment above the city’s iconic harbour. Sip on a glass of Taittinger and sample half a dozenSydney Rock Oysters while taking in the270-degree view that only gets better as the evening goes on. Available February 14-15, from $90.

Valentine’s Dinner at The Charles Brasserie, Sydney

For an indulgent, no detail spared Valentine’s Day supper, start your night with a glass of Ruinart Champagne Brut at The Charles Brasserie, situated right in the heart of Sydney, Next, indulge in head chef Billy Hannigan’s carefully curated three-course menu, which includes yellowfin tuna with confit tomato and fig leaf, premium Ranger Valley Wagyu with seasonal sides, and a ed berry and vanilla vacherin, accompanied by house-made petit fours. Available from 5pm at $165 per person.

Bar Morris, Sydney

Enjoy authentic Roman cuisine this Valentine’s Day, including from Morris’ signature house-made focaccia bread, eggplant involtini and Morris lasagna with slow-cooked bolognese ragu, ham and fiordilatte mozzarella. Nestled within Sydney’s lively CBD, this offer is only available on Friday, February 14.

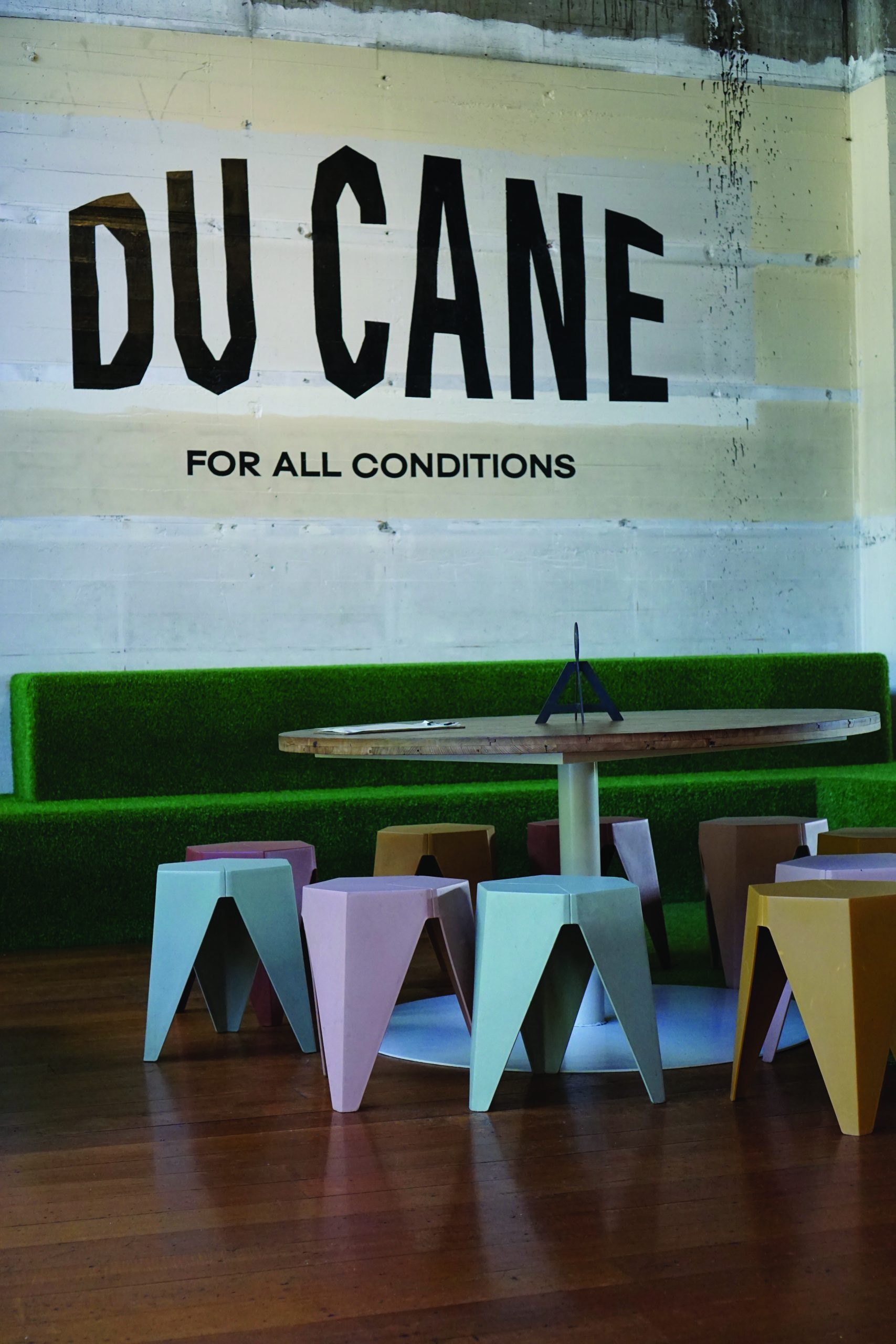

Harboard Hotel, Freshwater

If beach-bound romance is more your style, Harbord Hotel (located in Sydney’s Northern Beaches) channels a fiesta flair this year — you might even catch their mariachi band. Following a complimentary glass of Louis Roederer on arrival, spoil your special someone with Harboard Hotel’s exclusive four-course menu including a tartare of snapper, prawn roll and wagyu beef cheek, alongside pink beer and paloma specials. From $120 per person.

Peregrin, Merewether

If you’re situated around the Newcastle area and desire an elevated dining experience, set your maps for Merewether Beach and indulge in a four-course set menu and feast. Dishes include a Tartare of kingfish, Charcoal Roasted Huon salmon and triple cooked potatoes and Wagyu beef cheek – to a shared Raspberry Bombe Alaska for dessert, served with a complimentary glass of Louis Roederer. Available from 5pm, from $120 per person.

Photograph courtesy of Aster.

Photograph courtesy of Aster.  Malling used canvas from her studio as a tablecloth. Photograph by Charlotte de la Fuente

Malling used canvas from her studio as a tablecloth. Photograph by Charlotte de la Fuente

A new accommodation wing by Core Collective architects at the Georgian-era Leighton House in Evandale.

A new accommodation wing by Core Collective architects at the Georgian-era Leighton House in Evandale.

“My grandma used to make these,” said Lee Vasquez, at center, clapping, of the two tres leches cakes that the chef Isabel Garcia provided for dessert. Photograph by Su Cassiano.

“My grandma used to make these,” said Lee Vasquez, at center, clapping, of the two tres leches cakes that the chef Isabel Garcia provided for dessert. Photograph by Su Cassiano.

A birds eyed view of Headlands Hotel Austinmer Beach. Photograph courtesy of Headlands Hotel Austinmer Beach.

A birds eyed view of Headlands Hotel Austinmer Beach. Photograph courtesy of Headlands Hotel Austinmer Beach.

The designer Rolly Robínson, seated at top, hosted an intimate meal at a showroom in New York’s Chinatown. Photography by Linda Xiao.

The designer Rolly Robínson, seated at top, hosted an intimate meal at a showroom in New York’s Chinatown. Photography by Linda Xiao.